Nick Fuentes is a master of exploiting the current social media opportunities for extremism

- Written by Alex McPhee-Browne, PhD student studying the American and global far right, University of Cambridge

Right-wing influencer Nick Fuentes, center, speaks in front of flags that say 'America First' at a pro-Trump march on Nov. 14, 2020, in Washington. AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File

Right-wing influencer Nick Fuentes, center, speaks in front of flags that say 'America First' at a pro-Trump march on Nov. 14, 2020, in Washington. AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, FileWhen Tucker Carlson hosted Nick Fuentes on his show last month, the response followed a familiar script. Critics condemned the platforming of a white nationalist. Defenders invoked free speech. Social media erupted.

“We’ve had some great interviews with Tucker Carlson, but you can’t tell him who to interview,” President Donald Trump said on Nov. 17, 2025. “Ultimately, people have to decide.”

Fuentes is a 27-year-old livestreamer with openly antisemitic views. He has called Adolf Hitler both “awesome” and “right.” But he has become impossible for the Republican Party to banish, despite repeated attempts by some party leaders.

This dynamic reveals how fringe ideologies operate differently today compared to the mid-20th century, when institutional gatekeepers – political parties, law enforcement, the media – could more effectively contain extremist movements.

And through their 21st-century methods of communication and operation, Nick Fuentes and his followers – the “Groypers” – have managed to get what their 20th-century predecessors could not: widespread awareness and political influence.

Atlanta, 1940: Brazen but brief fascist group

As a historian of the American far right, I have spent years examining how fascist movements adapted to the conditions of postwar America. The trajectory from the 1940s until today shows a fundamental shift: from defined organizational structures that could be dismantled to diffuse cultural movements that spread through social media.

Let me offer an example.

In 1946, barely a year after Hitler’s defeat, young men in khaki shirts marched through Atlanta, Georgia, performing Nazi salutes and promising racial vengeance.

Led by Homer Loomis Jr. – a Princeton dropout who called Hitler’s manifesto “Mein Kampf” his “bible” – this group, known as the Columbians, offered Atlanta a glimpse of explicit fascism. They conducted armed patrols, held uniformed drills and even drew up blueprints for blowing up City Hall.

Their brazenness, however, was matched by their brevity. Ten months after forming, Atlanta authorities revoked their charter and jailed the ringleaders.

The swift suppression seemed to prove that explicit fascism had no future in postwar America. And for decades that held true. Open Nazi sympathizers remained marginal, their organizations small and easily ostracized.

In the 1970s, when a group of American Nazis planned to march in Skokie, Illinois, a predominantly Jewish suburb of Chicago, the event was most notable for the counterprotests it triggered.

Mainstreaming fascism

But the Columbians’ failure, it turned out, was organizational, not ideological. The government could revoke a charter and convict leaders. They could not repress a mood.

In the digital age, Fuentes represents that mood as a diffuse sensibility rather than a structured organization. Where the Columbians wore uniforms that advertised their fascist allegiance, Fuentes wears suits and frames his worldview in the rhetoric of “America First.”

The difference is strategic. In a 2019 livestream, Fuentes explained his approach openly: “Bit by bit we start to break down these walls … and then one day, we become the mainstream.”

This packaging marks a deliberate shift. Fuentes treats plausible deniability – of fascism, of antisemitism – not as a weakness but as a central feature. The content of his message remains extreme, but the ironic wrapping enables something the Columbians never achieved – cultural saturation.

Fuentes’s followers, Groypers, have in turn mastered this diffusion strategy.

For many conservatives under 40, exposure to Groyper-style content isn’t in meetings. They absorb it through social media feeds, Discord servers and group chats. A tone of grievance and ironic provocation becomes prominent background noise, moving the marginal toward the mainstream. A generation raised on anti-woke content, 4chan and transgressive memes now shapes the neofascist movement’s tone.

At the same time, institutional authority has in many ways effectively collapsed. The Columbians faced united opposition from media, prosecutors and politicians. Those gatekeepers no longer control conservatism or the white nationalists who are adjacent to it.

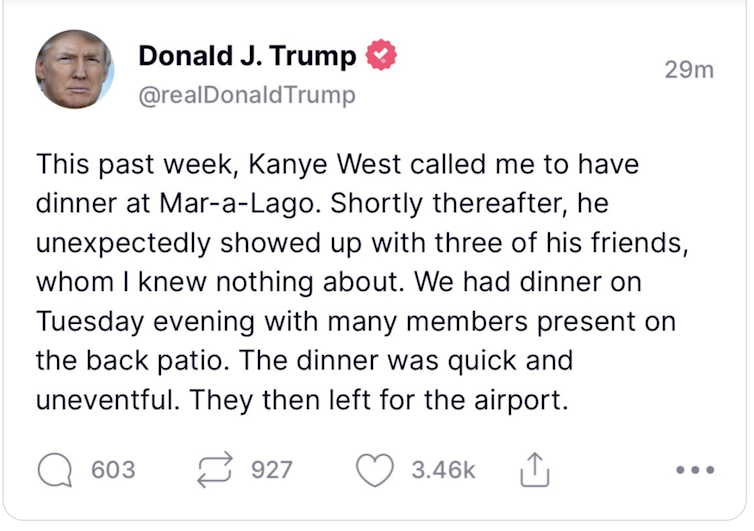

In late 2022, former President Donald Trump issued this social media post after having dinner with Nick Fuentes.X

In late 2022, former President Donald Trump issued this social media post after having dinner with Nick Fuentes.XAchieving what predecessors could not

The Carlson-Fuentes interview has instead exposed a rift within MAGA circles.

Several board members of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank with deep ties to the Trump administration, have resigned over the controversy, including one this week.

They were angered that Kevin Roberts, the foundation’s president, released a video defending the interview. Roberts has apologized for some of its contents but not retracted it.

Republicans aren’t all in agreement about whether Groypers represent a threat or an important constituency. Members of Congress have given speeches at Fuentes’ conferences; Trump dined with him at Mar-a-Lago in 2022.

Last year, JD Vance, now the vice president, called Fuentes a “total loser.” Fuentes attempted, without success, to mobilize Groypers against Trump in 2024 and called the president a “scam artist” earlier this year for failing to release the files in the Jeffrey Epstein case.

Yet the broader Groyperfication of conservative youth culture proceeds apace. Trump reversed his stance on the Epstein files. In defending Carlson’s interview with Fuentes, Trump said, “I don’t know much about him.”

Trump said roughly the same thing when he sat down to dinner with Fuentes at Mar-a-Lago in November 2022. Still, that event showed that the Groypers, now six years into their existence, have achieved what their predecessors could not: genuine cultural penetration and political influence.

The old remedies no longer function. Authorities cannot ban an atmosphere or revoke the charter of a meme. Social media platforms designed to maximize engagement often maximize anger. Fuentes and imitators exploit this frustration.

They remain controversial, and the Groypers’ lack of formal institutions could mean they will at some point fade like other far-right youth movements. Trump’s eventual exit from politics may also deprive them of a central reference point.

But they might represent something new: a post-organizational extremism uniquely adapted to digital life.

The Columbians once promised to control Atlanta in six months and America in 10 years. They lasted 10 months. The Groypers have already long outlasted them. That endurance signals a new, far more successful approach.

Alex McPhee-Browne does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Alex McPhee-Browne, PhD student studying the American and global far right, University of Cambridge