When the world’s largest battery power plant caught fire, toxic metals rained down – wetlands captured the fallout

- Written by Ivano W. Aiello, Professor of Marine Geology, San José State University

A battery energy storage facility that was built inside an old power plant burned from Jan. 16-18, 2025.Mike Takaki

A battery energy storage facility that was built inside an old power plant burned from Jan. 16-18, 2025.Mike TakakiWhen fire broke out at the world’s largest battery energy storage facility in January 2025, its thick smoke blanketed surrounding wetlands, farms and nearby communities on the central California coast.

Highways closed, residents evacuated and firefighters could do little but watch as debris and ash rained down. People living in the area reported headaches and respiratory problems, and some pets and livestock fell ill.

Two days later, officials announced that the air quality met federal safety standards. But the initial all-clear decision missed something important – heavy metal fallout on the ground.

A chunk of charred battery debris found near bird tracks in the mud, with a putty knife to show the size. The surrounding marshes are popular stopovers for migrating seabirds. Scientists found a thin layer of much smaller debris across the wetlands.Ivano Aiello, et al, 2025

A chunk of charred battery debris found near bird tracks in the mud, with a putty knife to show the size. The surrounding marshes are popular stopovers for migrating seabirds. Scientists found a thin layer of much smaller debris across the wetlands.Ivano Aiello, et al, 2025When battery energy storage facilities burn, the makeup of the chemical fallout can be a mystery for surrounding communities. Yet, these batteries often contain metals that are toxic to humans and wildlife.

The smoke plume from the fire in Vistra’s battery energy storage facility at Moss Landing released not just hazardous gases such as hydrogen fluoride but also soot and charred fragments of burned batteries that landed for miles around.

I am a marine geologist who has been tracking soil changes in marshes adjacent to the Vistra facility for over a decade as part of a wetland-restoration project. In a new study published in the journal Scientific Reports, my colleagues and I were able to show through detailed before-and-after samples from the marshes what was in the battery fire’s debris and what happened to the heavy metals.

The batteries’ metal fragments, often too tiny to see with the naked eye, didn’t disappear. They continue to be remobilized in the environment today.

The Vistra battery energy storage facility – the large gray building in the lower left, near Monterey Bay – is surrounded by farmland and marshes. The smoke plume from the fire rained ash on the area and reached four counties.Google Earth, with data from Google, Airbus, MBARI, CSUMB, CC BY

The Vistra battery energy storage facility – the large gray building in the lower left, near Monterey Bay – is surrounded by farmland and marshes. The smoke plume from the fire rained ash on the area and reached four counties.Google Earth, with data from Google, Airbus, MBARI, CSUMB, CC BYWhat’s inside the batteries

Moss Landing, at the edge of Monterey Bay, has long been shaped by industry – a mix of power generation and intensive agriculture on the edge of a delicate coastal ecosystem.

The Vistra battery storage facility rose on the site of an old Duke Energy and PG&E gas power plant, which was once filled with turbines and oil tanks. When Vistra announced it was converting the site into the world’s largest lithium-ion battery facility, the plan was hailed as a clean energy milestone. Phase 1 alone housed batteries with 300 megawatts of capacity, enough to power about 225,000 homes for four hours.

The energy in rechargeable batteries comes from the flow of electrons released by lithium atoms in the anode moving toward the cathode.

In the type of batteries at the Moss Landing facility, the cathode was rich in three metals: nickel, manganese and cobalt. These batteries are prized for their high energy density and relatively low cost, but they are also prone to thermal runaway.

Lab experiments have shown that burning batteries can eject metal particles like confetti.

Metals found in wetlands matched batteries

When my team and I returned to the marsh three days after the fire, ash and burned debris covered the ground. Weeks afterward, charred fragments still clung to the vegetation.

Our measurements with portable X-ray fluorescence showed sharp increases in nickel, manganese and cobalt compared with data from before the fire. As soon as we saw the numbers, we alerted officials in four counties about the risk.

We estimate that about 25 metric tons (55,000 pounds) of heavy metals were deposited across roughly half a square mile (1.2 square kilometers) of wetland around Elkorn Slough, and that was only part of the area that saw fallout.

To put this in perspective, the part of the Vistra battery facility that burned was hosting 300 megawatts of batteries, which equates to roughly 1,900 metric tons of cathode material. Estimates of the amount of batteries that burned range from 55% to 80%. Based on those estimates, roughly 1,000 to 1,400 metric tons of cathode material could have been carried into the smoke plume. What we found in the marsh represents about 2% of what may have been released.

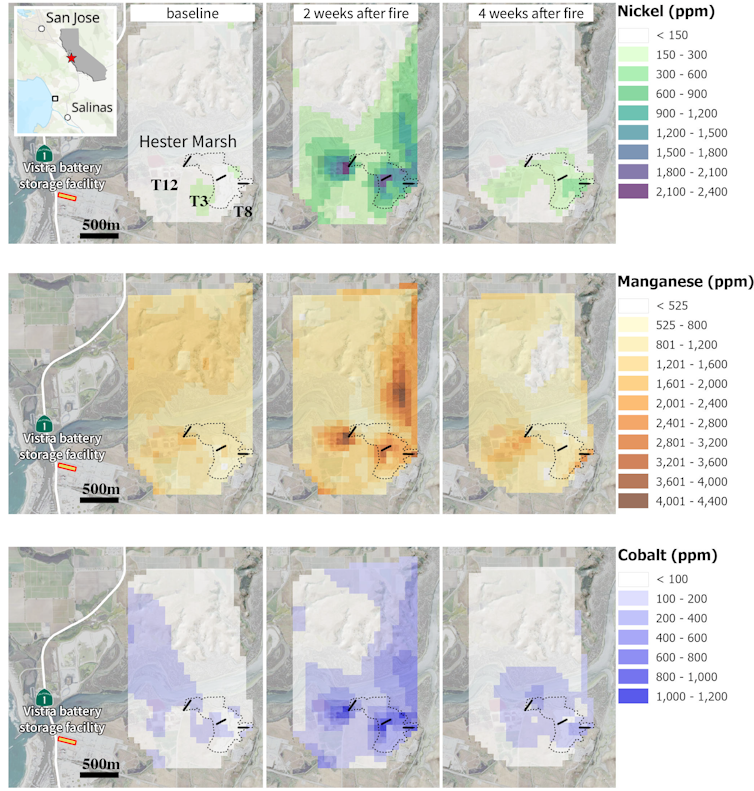

These contour maps show how metals from the Moss Landing battery fire settled across nearby wetlands. Each color represents how much of a metal – nickel, manganese or cobalt – was found in surface soils. Darker colors mean higher concentrations. The highest levels were measured about two weeks after the fire, then declined as rain and tides dispersed the deposits.Charlie Endris

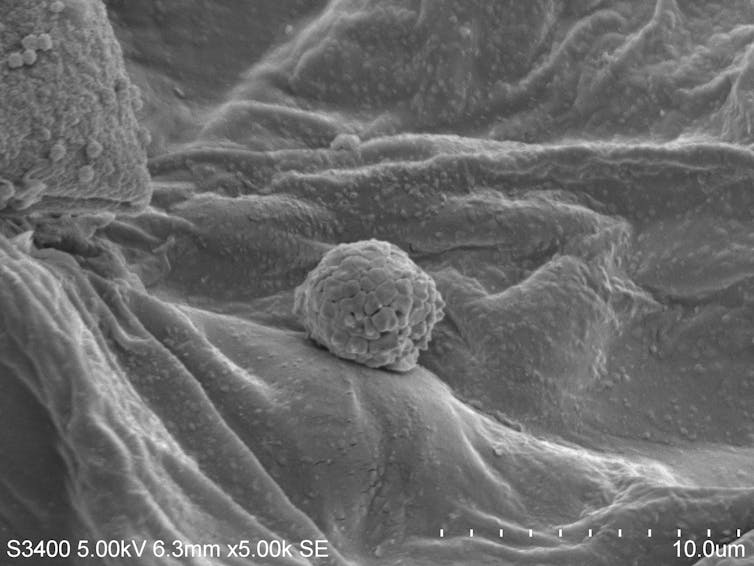

These contour maps show how metals from the Moss Landing battery fire settled across nearby wetlands. Each color represents how much of a metal – nickel, manganese or cobalt – was found in surface soils. Darker colors mean higher concentrations. The highest levels were measured about two weeks after the fire, then declined as rain and tides dispersed the deposits.Charlie EndrisWe took samples at hundreds of locations and examined millimeter-thin soil slices with a scanning electron microscope. Those slices revealed metallic particles smaller than one-tenth the width of a human hair – small enough to travel long distances and lodge deep in the lungs.

The ratio of nickel to cobalt in these particles matched that of nickel, manganese and cobalt battery cathodes, clearly linking the contamination to the fire.

Over the following months, we found that surface concentrations of the metals dropped sharply after major rain and tidal events, but the metals did not disappear. They were remobilized. Some migrated to the main channel of the estuary and may have been flushed out into the ocean. Some of the metals that settled in the estuary could enter the food chain in this wildlife hot spot, often populated with sea otters, harbor seals, pelicans and herons.

A high-magnification image of a leaf of bristly oxtongue, seen under a scanning electron microscope, shows a tiny metal particle typically used in cathode material in lithium-ion batteries, a stark reminder that much of the fallout from the fire landed on vegetation and croplands. The image’s scale is in microns: 1 micron is 0.001 millimeters.Ivano Aiello

A high-magnification image of a leaf of bristly oxtongue, seen under a scanning electron microscope, shows a tiny metal particle typically used in cathode material in lithium-ion batteries, a stark reminder that much of the fallout from the fire landed on vegetation and croplands. The image’s scale is in microns: 1 micron is 0.001 millimeters.Ivano AielloMaking battery storage safer as it expands

The fire at Moss Landing and its fallout hold lessons for other communities, first responders and the design of future lithium-ion battery systems, which are proliferating as utilities seek to balance renewable power and demand peaks.

When fires break out, emergency responders need to know what they’re dealing with. A California law passed after the fire helps address this by requiring strengthening containment and monitoring at large battery installations and meetings with local fire officials before new facilities open.

How lithium-ion batteries work, and why they can be prone to thermal runaway.Newer lithium-ion batteries that use iron phosphate cathodes are also considered safer from fire risk. These are becoming more common for utility-scale energy storage than batteries with nickel, manganese and cobalt, though they store less energy.

How soil is tested is also important. At Moss Landing, some of the government’s sampling turned up low concentrations of the metals, likely because the samples came from broad, mixed layers that diluted the concentration of metals rather than the thin surface deposits where contaminants settled.

Continuing risks to marine life

Metals from the Moss Landing battery fire still linger in the region’s sediments and food webs.

These metals bioaccumulate, building up through the food chain: The metals in marsh soils can be taken up by worms and small invertebrates, which are eaten by fish, crabs or shorebirds, and eventually by top predators such as sea otters or harbor seals.

Our research group is now tracking the bioaccumulation in Elkhorn Slough’s shellfish, crabs and fish. Because uptake varies among species and seasons, the effect of the metals on ecosystems will take months or years to emerge.

Ivano Aiello receives funding from private donors.

Authors: Ivano W. Aiello, Professor of Marine Geology, San José State University