Measuring Colorado’s mountains one hike at a time

- Written by Eric Gilbertson, Associate Teaching Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Seattle University

Using lightweight tools, Eric Gilbertson hikes the world's tallest mountains to measure their heights. Elijah Gendron

Using lightweight tools, Eric Gilbertson hikes the world's tallest mountains to measure their heights. Elijah GendronIn the middle of a chilly October night in 2025, my two friends and I suited up at the Cottonwood Creek trailhead and started a trek into the Sangre de Cristo mountains of Colorado. It was a little below freezing as we got moving at 1:30 a.m., and the Moon illuminated the snowy mountaintops above us.

Our packs were a bit heavier than normal because we were hauling highly accurate surveying equipment to the summits of two peaks, each over 14,000 feet (4,267.2 meters). The peaks, Crestone and East Crestone, were close enough in height, with a short enough saddle in between, that only the taller of the two would count as a true 14er and the other as a sub-peak.

Crestone had traditionally been thought to be taller and sees hundreds of ascents each year. East Crestone, traditionally believed to be shorter, sees only a fraction as many ascents. Colorado has 58 mountain peaks over 14,000 feet that peakbaggers consider 14ers. For locals and visitors alike, bagging a 14er is a sport, and some people post reports about having climbed all 58.

I wanted to measure which was taller, since I suspected previous measurements people had trusted for years might be erroneous.

GPS allows Eric Gilbertson to measure the peaks of Crestone and East Crestone in Colorado in October 2025.Eric Gilbertson

GPS allows Eric Gilbertson to measure the peaks of Crestone and East Crestone in Colorado in October 2025.Eric GilbertsonI teach mountain surveying, and I climb and research mountains around the world for fun. I’m trying to climb the highest mountain in every country on Earth. I have so far climbed 147 of 196, including tough, high-altitude technical ones such as K2 without supplemental oxygen in Pakistan and Pobeda in Kyrgyzstan.

Through my experience climbing, I discovered that not all countries in the world have been surveyed accurately enough to know the country’s true high point. The high point is geographically significant, as it’s the highest natural point or peak in the country, state or province. Often, high points are a source of national or state pride. I taught myself surveying to determine and verify these high points on my own.

Discovering high points around the world

I’ve so far discovered new high points in seven countries: Colombia – Pico Simón Bolívar; Saudi Arabia – Jabal Ferwa; Uzbekistan – Alpomish; Togo – Mount Atilakoutse; Gambia – Sare Firasu Hill; Guinea Bissau – Mount Ronde; and Botswana – Monalanong Hill.

Ginge Fullen, a climbing partner of Eric Gilbertson, sits atop the peak of Pico Simon Bolivar in Colombia in December 2024.Eric Gilbertson

Ginge Fullen, a climbing partner of Eric Gilbertson, sits atop the peak of Pico Simon Bolivar in Colombia in December 2024.Eric GilbertsonI’ve surveyed over 60 peaks in the U.S. and Canada. In 2025 I discovered a new state high point in Michigan, Mount Curwood, at 1,979.3 feet (603.3 meters), and a new provincial high point of Nova Scotia, Western Barren, at 1,743.2 feet (531.3 meters).

I’ve determined the 100 highest peaks in Washington state, where I live and work, and studied how climate change is affecting the elevations of ice-capped peaks. My research showed that, while historically the contiguous U.S. had five ice-capped peaks, only two remain – Liberty Cap and Colfax, both in Washington state. Mount Rainier used to have as its highest point an ice dome named Columbia Crest on the western rim of the summit crater. But since 1998, Columbia Crest has melted more than 20 feet (6 meters) and is no longer the highest point on the mountain. The highest point is now a rock 436 feet (133 meters) to the south, on the southwest edge of the summit crater.

At the very top of South Mirror Image Peak in Washington, Eric Gilbertson uses an Abney level to measure nearby mountain heights.Matthew Gilbertson

At the very top of South Mirror Image Peak in Washington, Eric Gilbertson uses an Abney level to measure nearby mountain heights.Matthew GilbertsonHow to survey mountain high points

Surveying mountains is challenging due to the altitude, long approaches, difficult weather conditions and technical climbing. To get accurate surveying equipment to the summits requires ingenuity and specialized gear. Equipment needs to be as light as possible and adaptable to tricky terrain. For these reasons, very few mountains have been surveyed to the level of accuracy I can attain.

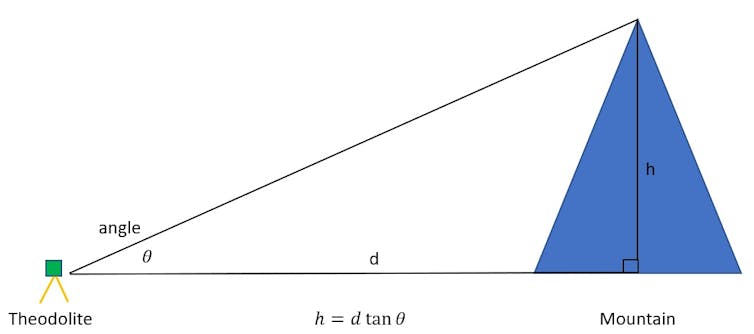

Historically, measurements have generally been made from a distance with theodolites. These are mechanical devices that can measure an angle up to a mountain summit very accurately. The distance to the mountain can be measured by other means, and trigonometry can be used with the distance and angle to calculate the summit elevation. But if the measurement is taken too far away, the error in elevation can be high. Theodolites are heavy and not easy to carry close to a peak.

Schematic diagram of how a theodolite is used to measure an angle to the summit of a mountain.Eric Gilbertson

Schematic diagram of how a theodolite is used to measure an angle to the summit of a mountain.Eric GilbertsonI sometimes carry a 30-pound (13.61 kg) theodolite to a summit, but if the mountain is technical, this is challenging and requires complicated rope systems to haul it up. More often I bring an Abney level, which is a lighter mechanical device that also measures angles. I bring this to a summit to measure relative angles between nearby points to identify which is the highest point on the mountain.

A theodolite is a mechanical devices that can measure angles up to a summit very accurately. Here one is used on Cardinal Peak in Washington in June 2023.Eric Gilbertson

A theodolite is a mechanical devices that can measure angles up to a summit very accurately. Here one is used on Cardinal Peak in Washington in June 2023.Eric GilbertsonI then use a highly accurate, survey-grade GPS to measure the absolute elevation of the highest point. The GPS requires an hour or more to get an accurate measurement, so it wouldn’t make sense timewise to measure many nearby points with this device. I’ve found time is usually limited when surveying a summit, due to incoming storms or approaching darkness when descents need to be made in daylight for safety. This is why I first identify the highest point with an Abney level or theodolite.

Many satellites overhead send data down that is collected by the GPS device and used to calculate the device’s position. To save weight, I use a device that then sends measurements over Bluetooth to my phone instead of requiring a dedicated computer.

A GPS receiver generally needs to be mounted on a vertical rod that touches the exact summit. I measure the GPS height, subtract the rod height, and that gives the summit height. To keep the rod perfectly vertical I use a tripod, and this also requires innovation.

Eric Gilbertson uses a GPS to measure East Fury in Washington.Courtesy of Ross Wallette

Eric Gilbertson uses a GPS to measure East Fury in Washington.Courtesy of Ross WalletteSometimes a summit is so sharp that regular tripod legs aren’t long enough to touch the ground. In this case, I strap on hiking poles to extend the legs. Another solution is to use a tripod with flexible legs, and I mold the legs to conform to the shape of a sharp boulder. This is what I used to measure the high point of Uzbekistan.

Another tool I use is LiDAR, which stands for light detection and ranging. This works by an airplane flying over a mountain and bouncing light signals off the summit. By using the plane’s location and the time it takes the signal to bounce back, the mountain’s elevation can be calculated.

Colorado 14ers

All measurements can have errors. I traveled to Colorado because I suspected LiDAR measurements of Crestone Peak, considered a 14er, might be erroneous. LiDAR measurements have been taken for nearly all mountains in Colorado, and these measurements are generally the most accurate available for mountain elevations.

LiDAR measurements hit the ground every few feet of horizontal spacing and can miss the top of sharp summits, leading to an underestimate of summit height. They can also hit things such as bushes, leading to an overestimate of summit height.

LiDAR data showed Crestone Peak and East Crestone within a few feet of the same height. But, interestingly, it showed a 3-4 foot (0.9-1.2 meter) spike on the top of Crestone. I climbed Crestone in 2020 while doing the Rocky Mountain Slam, a challenge to climb all the Colorado 14ers, Wyoming 13ers and Montana 12ers in two months, and knew the summit was pretty flat. I speculated that spike could have easily been a person, which meant the LiDAR elevation of Crestone might be too high.

East Crestone has a sharp boulder on the summit, which LiDAR could easily miss because of the horizontal gaps between measurements. So that elevation was possibly too short. In Colorado a point needs 300 feet (91.44 meters) of prominence to count as a separate peak. Other states have different rules, like in Washington where 400 feet (121.92 meters) is required. Prominence is a measure of how high a peak sticks up above a saddle connecting it to a taller peak. The saddle between Crestone and East Crestone is short enough that only the taller of them is a true peak and the other is a sub-peak.

On East Crestone I first set up a tall tripod, but the wind blew it down, nearly over a cliff. I switched it out with a shorter one, which was more stable.

Eric Gilbertson hiked Crestone, one of Colorado’s 14ers, to determine its true height.Elijah Gendron

Eric Gilbertson hiked Crestone, one of Colorado’s 14ers, to determine its true height.Elijah GendronI then scrambled over to Crestone Peak and mounted another identical GPS device. That summit was on the edge of a cliff, and I needed to extend one tripod leg with a hiking pole so it could touch the ground.

I logged data for over two hours with both devices simultaneously. This ensured both were receiving the same satellite signals – so any atmospheric distortion would be the same – and that enough data was logged so I could get elevations accurate to the nearest inch. This gave me a lot of time to admire the views and take pictures, but I also needed to check on the equipment every 5-10 minutes to ensure it was working properly.

After packing up, hiking down and flying home to Seattle, I spent a few weeks poring over the data. The results showed East Crestone is 0.3 feet (0.09 meters) taller than Crestone, with more than 99.9% confidence that East Crestone is taller.

This means Colorado has a new 14er: East Crestone. Crestone is, in fact, a sub-peak. Discussions are ongoing about whether this means the 14ers list that peakbaggers climb should retain Crestone and add East Crestone to be 59 peaks, or whether East Crestone should replace Crestone so the list stays at 58 peaks.

I’m planning to continue my work surveying mountains in Colorado and around the world to determine accurate summit elevations. My next plan is surveying several country high points in Africa this winter. The Benin country high point is still not known, and I hope to solve that mystery next.

Read more of our stories about Colorado.

Eric Gilbertson receives funding from The American Alpine Club.

Authors: Eric Gilbertson, Associate Teaching Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Seattle University

Read more https://theconversation.com/measuring-colorados-mountains-one-hike-at-a-time-269343