Almost half of young workers expected to work unpaid overtime, while a quarter aren’t paid compulsory super

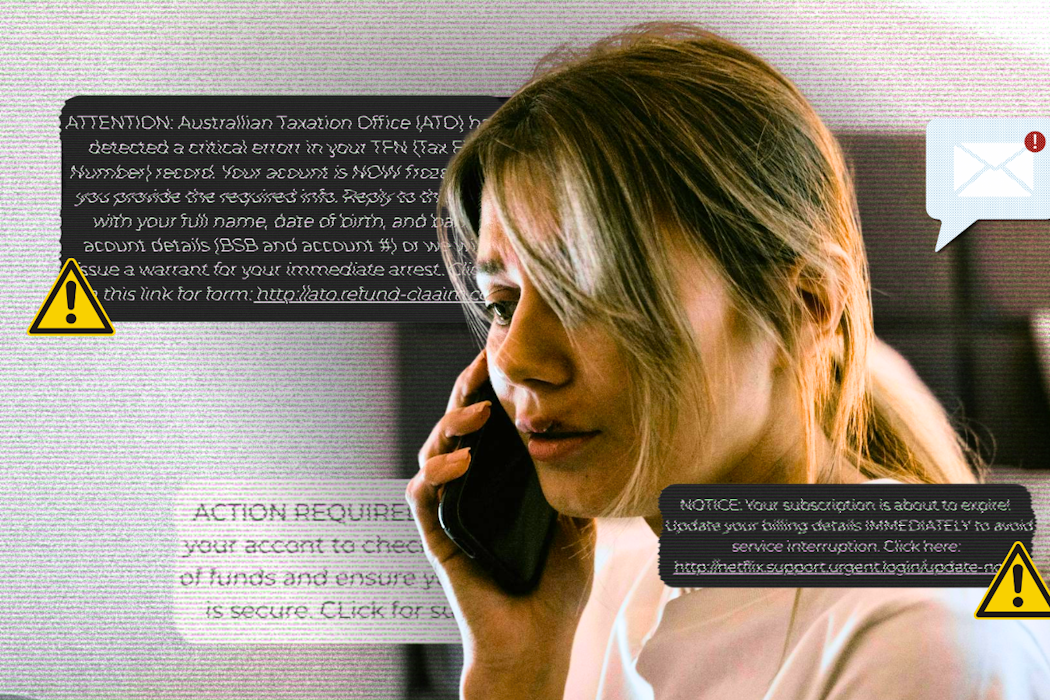

A young person gets a job, excited to earn their first paycheck. Over time, they realise the hours are long and the payslips small. They are told to stay back to clean up after closing, but never receive overtime. They feel exploited, but what can they do?

It’s hard to find a job that fits with study commitments, and a reference could go a long way in the future. Besides, it happens to all their co-workers; they’d hate to cause a fuss.

It’s a story as old as time, and it’s still happening today. Our new study has found wage exploitation is rife among employers who hire young people.

In partnership with the Paul Ramsay Foundation, Melbourne Law School’s Fair Day’s Work project surveyed 2,814 workers under 30.

Young workers in low-paid jobs were asked about their experiences in the workplace, the challenges they encountered, and how they dealt with exploitation.

How some bosses are treating young workers

We found young Australians are frequently underpaid and that exploitation is multifaceted:

33% were paid $15 per hour or less

43% had been told to complete extra work without additional pay

34% were not paid for work during a trial period

24% had not received compulsory super

35% had their timesheet hours reduced by their employer

17.9% had not been paid for all the work they completed

9% received an hourly rate of $10 or less

8% had been forced to return some, or all, of their pay to their employer.

Further, 60% had had to pay for work-related items, such as uniforms, protective equipment, training or car fuel. Some 36% had been forbidden to take entitled breaks while 35% had their recorded timesheet hours reduced by their employer. Meanwhile 20% were “sometimes” paid “off the books”, and 12% were “always” paid off the books. And 9.5% had been given food or products instead of being paid in money.

The most at risk

We found exploitation is most often experienced by the most vulnerable young people. These include transgender, non-permanent workers (casual employees and private contractors), residents on temporary visas) and non-native English speakers.

The worst-performing industries included electricity, gas, water and waste services; manufacturing; mining; transport, postal and warehousing; public administration and safety; information media and telecommunications; accommodation and food services; retail trade, and education and training.

Workers in small businesses (up to 19 staff) were often not paid overtime or penalty rates, and were being paid “off the books”.

Medium-sized business workers (20–199 employees) were the most likely to be required to pay for work-related items, such as equipment, training and car hire.

And those from large businesses (200-plus) reported the highest rates of variance of weekly hours and requirements to pay for work uniform.

Young people often don’t have much industrial knowledge or experience, so it is easy for employers to take advantage of them. They are also unlikely to challenge an employer, as many of them are in insecure work.

What steps are being taken?

Laws which took effect January 1 this year mean employers may face criminal penalties – including fines, imprisonment or both – if they intentionally underpay an employee in breach of the Fair Work Act 2009.

But identifying underpayments and other forms of exploitation are the biggest barrier to compliance with workplace laws.

Surveyed workers who were underpaid said they were most likely to seek the help of a family member. Only 12.9% of those aged 15 to 19 said they would be willing to complain to the Fair Work Ombudsman.

However, workers who had dealt with the ombudsman mostly saw their experiences as positive: 41% found the regulator to be “very helpful”, while only 16.7% described it as “not helpful at all” or “not very helpful”.

The results suggest the Fair Work Ombudsman needs to be doing more to engage teenage workers.

What’s needed

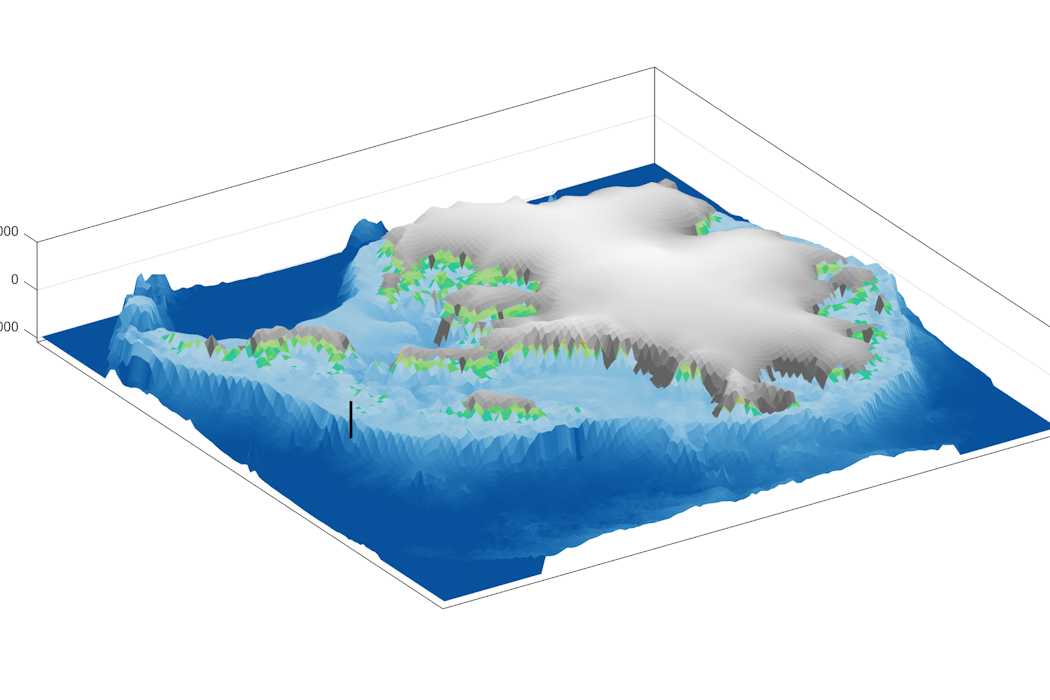

The Fair Day’s Work project set out to use data science and technology to identify risk of underpayment in relation to young workers, and improve employer compliance with workplace laws.

Our aim was to develop a database on young workers employment conditions, along with a web portal to give young people and employers the information they need.

We hypothesised that a prediction tool could be used to assess which young workers are at greatest risk. However, we found publicly available data was insufficient to do this, so we conducted our own survey of young workers and made this data available through a public web portal to help workers and employers.

We came up six recommendations to help stop young workers being exploited:

regulators need to get tougher with the nine industries we identified as the poorest performers to make them more compliant

the Fair Work Ombudsman should scrutinise the industries where payment was made in food or products and workers were required to return money to employers occurred most frequently

educate mid-sized businesses on the extent to which they can lawfully require workers to pay for work-related items

lawmakers and the Fair Work Commission should consider introducing truly equitable “loaded rates” for junior employees. This would deal with non-payment of penalty rates and other entitlements by some employers

more money to make young workers aware they can get help from the Fair Work Ombudsman, trade unions, community legal centres, the Young Workers’ Centre and similar bodies

more work to develop and use data science and digital tools to help employers fulfil their legal obligations, and to protect young workers’ rights.

Our survey results highlight the extent to which young people continue to be exploited in the workplace and suggest more work needs to be done to bring about change.

Authors: The Conversation