Censorship campaigns can have a way of backfiring – look no further than the fate of America’s most prolific censor

- Written by Amy Werbel, Professor of the History of Art, Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT)

The vast majority of Americans support the right to free speech.Jacek Boczarski/Anadolu via Getty Images

The vast majority of Americans support the right to free speech.Jacek Boczarski/Anadolu via Getty ImagesIn the first year of President Donald Trump’s second term in office, his administration has made many attempts to suppress speech it disfavors – at universities, on the airwaves, in public school classrooms, in museums, at protests and even in lawyer’s offices.

If past is prologue, these efforts may backfire.

In 2018, I published my book “Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock.”

A devout evangelical Christian, Comstock hoped to use the powers of the government to impose moral standards on American expression in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. To that end, he and like-minded donors established the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which successfully lobbied for the creation of the first federal anti-obscenity laws with enforcement provisions.

Later appointed inspector for the Post Office Department, Comstock fought to abolish whatever he deemed blasphemous and sinful: birth control, abortion aids and information about sexual health, along with certain art, books and newspapers. Federal and state laws gave him the power to order law enforcement to seize these materials and have prosecutors bring criminal indictments.

I analyzed thousands of these censorship cases to assess their legal and cultural outcomes.

I found that, over time, Comstock’s censorship regime did lead to a rise in self-censorship, confiscations and prosecutions. However, it also inspired greater support for free speech and due process.

More popular – and more profitable

One effect of Comstock’s censorship campaigns: The materials and speech he disfavored often made headlines, putting them on the public’s radar as a kind of “forbidden fruit.”

For example, prosecutions targeting artwork featuring nude subjects led to both sensational media coverage and a boom in the popularity of nudes on everything from soap advertisements and cigar boxes to photographs and sculptures.

Anthony Comstock.Bettmann/Getty Images

Anthony Comstock.Bettmann/Getty ImagesMeanwhile, entrepreneurs of racy forms of entertainment – promoters of belly dancing, publishers of erotic postcards and producers of “living pictures,” which were exhibitions of seminude actors posing as classical statuary – all benefited from Comstock’s complaints. If Comstock wanted it shut down, the public often assumed that it was fun and trendy.

In 1891, Comstock became irate when a young female author proposed paying him to attack her book and “seize a few copies” to “get the newspapers to notice it.” And in October 1906, Comstock threatened to shut down an exhibition of models performing athletic exercises wearing form-fitting union suits. Twenty thousand people showed up to Madison Square Garden for the exhibition – far more than the venue could hold at the time.

The Trump administration’s recent efforts to get comedian Jimmy Kimmel off the air have similarly backfired.

Kimmel had generated controversy for comments he made on his late-night talk show in the wake of conservative activist Charlie Kirk’s assassination. ABC, which is owned by The Walt Disney Co., initially acquiesced to pressure from Federal Communications Commission Chairman Brendan Carr and announced the show’s “indefinite” suspension. But many viewers, angered over the company’s capitulation, canceled their subscriptions of Disney streaming services. This led to a 3.3% drop in Disney’s share price, which spurred legal actions by shareholders of the publicly traded company.

ABC soon lifted the suspension. Kimmel returned, drawing 6.26 million live viewers – more than four times his normal audience – while over 26 million viewers watched Kimmel’s return monologue on social media. Since then, all network affiliates have resumed airing “Jimmy Kimmel Live!”

‘Comstockery’ and hypocrisy

In the U.S., disfavored political speech and obscenity are different in important ways. The Supreme Court has held that the First Amendment provides broad protections for political expression, whereas speech deemed to be obscene is illegal.

Despite this fundamental difference, social and cultural forces can make it difficult to clearly discern protected and unprotected speech.

In Comstock’s case, the public was happy to see truly explicit pornography removed from circulation. But their own definition of what was “obscene” – and, therefore, criminally liable – was much narrower.

In 1905, Comstock attempted to shut down a theatrical performance of George Bernard Shaw’s “Mrs. Warren’s Profession” because the plot included prostitution. The aging censor was widely ridiculed and became a “laughing stock,” according to The New York Times. Shaw went on to coin the term “Comstockery,” which caught on as a shorthand for overreaching censoriousness.

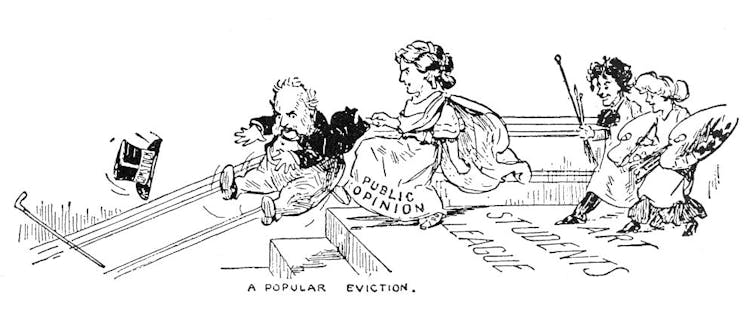

Cartoonists at the turn of the 20th century had a field day with Anthony Comstock’s overreaches.Amazon

Cartoonists at the turn of the 20th century had a field day with Anthony Comstock’s overreaches.AmazonIn a similar manner, when Attorney General Pam Bondi recently threatened Americans that the Department of Justice “will absolutely … go after you, if you are targeting anyone with hate speech,” swift backlash ensued.

Numerous Supreme Court rulings have held that hate speech is constitutionally protected. However, those in power can threaten opponents with punishment even when their speech clearly does not fall within one of the rare exceptions to the First Amendment protection for political speech.

Doing so carries risks.

The old saying “people in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones” also applies to censors: The public holds them to higher standards, lest they be exposed as hypocrites.

For critics of the Trump administration, it was jarring to see officials outraged about “hate speech,” only to hear the president announce, at Charlie Kirk’s memorial, “I hate my opponent, and I don’t want the best for them.”

In Comstock’s case, defendants and their attorneys routinely noted that Comstock had seen more illicit materials than any man in the U.S. Criticizing Comstock in 1882, Unitarian minister Octavius Brooks Frothingham quoted Shakespeare: “Who is so virtuous as to be allowed to forbid the distribution of cakes and ale?”

In other words, if you’re going to try to enforce moral standards, you better make sure you’re beyond reproach.

Free speech makes for strange bedfellows

Comstock’s censorship campaign, though self-defeating in the long run, nonetheless caused enormous suffering, just as many people today are suffering from calls to fire and harass those whose viewpoints are legal, but disliked by the Trump administration.

Comstock prosecuted women’s rights advocate Ida Craddock for circulating literature that advocated for female sexual pleasure. After Craddock was convicted in 1902, she died by suicide. She left behind a “letter to the public,” in which she accused Comstock of violating her rights to freedom of religion and speech.

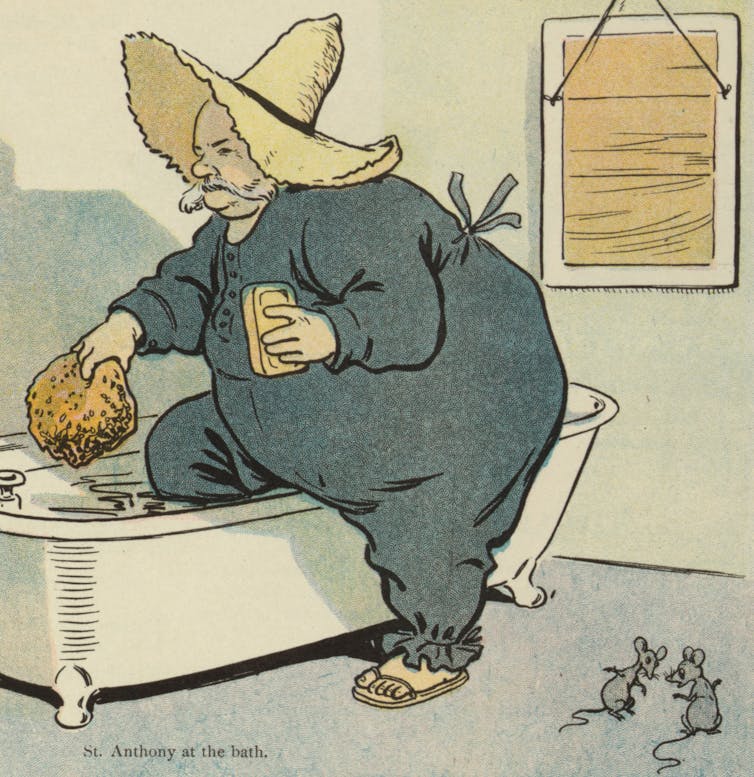

A 1906 cartoon in the satirical periodical Puck mocks Anthony Comstock as a prude.PhotoQuest/Getty Images

A 1906 cartoon in the satirical periodical Puck mocks Anthony Comstock as a prude.PhotoQuest/Getty ImagesDuring Craddock’s trial, the jury hadn’t been permitted to see her writings; they were deemed “too harmful.” Incensed by these violations of the First and Fourth amendments, defense attorneys rallied together and were joined by a new coalition in the support of Americans’ constitutional rights. Lincoln Steffens of the nascent Free Speech League wrote, in response to Craddock’s suicide, that “those who believe in the general principle of free speech must make their point by supporting it for some extreme cause. Advocating free speech only for a popular or uncontroversial position would not convey the breadth of the principle.”

Then, as now, the cause of free expression can bring together disparate political factions.

In the wake of the Kimmel saga, many conservative Republicans came out to support the same civil liberties also advocated by liberal Hollywood actors. Two-thirds of Americans in a September 2025 YouGov poll said that it was “unacceptable for government to pressure broadcasters to remove shows it disagrees with.”

My conclusion from studying the 43-year career of America’s most prolific censor?

Government officials may think a campaign of suppression and fear will silence their opponents, but these threats could end up being the biggest impediment to their effort to remake American culture.

Amy Werbel receives funding from the State University of New York.

Authors: Amy Werbel, Professor of the History of Art, Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT)