Where George Washington would disagree with Pete Hegseth about fitness for command and what makes a warrior

- Written by Maurizio Valsania, Professor of American History, Università di Torino

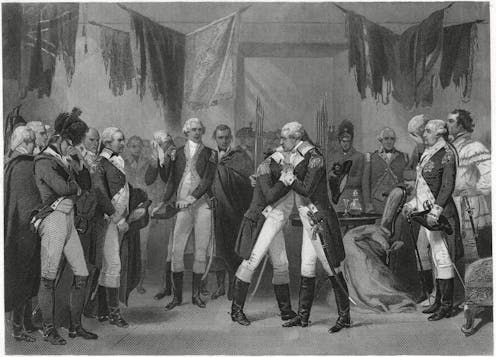

On Dec. 4, 1783, after six years fighting against the British as head of the Continental Army, George Washington said farewell to his officers and returned to civilian life.Engraving by T. Phillibrown from a painting by Alonzo Chappell

On Dec. 4, 1783, after six years fighting against the British as head of the Continental Army, George Washington said farewell to his officers and returned to civilian life.Engraving by T. Phillibrown from a painting by Alonzo ChappellAs he paced across a stage at a military base in Quantico, Virginia, on Sept. 30, 2025, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth told the hundreds of U.S. generals and admirals he had summoned from around the world that he aimed to reshape the military’s culture.

Ten new directives, he said, would strip away what he called “woke garbage” and restore what he termed a “warrior ethos.”

The phrase “warrior ethos” – a mix of combativeness, toughness and dominance – has become central to Hegseth’s political identity. In his 2024 book “The War on Warriors,” he insisted that the inclusion of women in combat roles had drained that ethos, leaving the U.S. military less lethal.

In his address, Hegseth outlined what he sees as the qualities and virtues the American soldier – and especially senior officers – should embody.

On physical fitness and appearance, he was blunt: “It’s completely unacceptable to see fat generals and admirals in the halls of the Pentagon and leading commands around the country and the world.”

He then turned from body shape to grooming: “No more beardos,” Hegseth declared. “The era of rampant and ridiculous shaving profiles is done.”

As a historian of George Washington, I can say that the commander in chief of the Continental Army, the nation’s first military leader, would have agreed with some of Secretary Hegseth’s directives – but only some.

Washington’s overall vision of a military leader could not be further from Hegseth’s vision of the tough warrior.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth speaks to senior military leaders at Marine Corps Base Quantico on Sept. 30, 2025.Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth speaks to senior military leaders at Marine Corps Base Quantico on Sept. 30, 2025.Andrew Harnik/Getty Images280 pounds – and trusted

For starters, Washington would have found the concern with “fat generals” irrelevant. Some of the most capable officers in the Continental Army were famously overweight.

His trusted chief of artillery, Gen. Henry Knox, weighed around 280 pounds. The French officer Marquis de Chastellux described Knox as “a man of thirty-five, very fat, but very active, and of a gay and amiable character.”

Others were not far behind. Chastellux also described Gen. William Heath as having “a noble and open countenance.” His bald head and “corpulence,” he added, gave him “a striking resemblance to Lord Granby,” the celebrated British hero of the Seven Years’ War. Granby was admired for his courage, generosity and devotion to his men.

Washington never saw girth as disqualifying. He repeatedly entrusted Knox with the most demanding assignments: designing fortifications, commanding artillery and orchestrating the legendary “noble train of artillery” that brought cannon from Fort Ticonderoga to Boston.

When he became president, after the Revolution, Washington appointed Knox the first secretary of war – a sign of enduring confidence in his judgment and integrity.

Beards: Outward appearance reflects inner discipline

As for beards, Washington would have shared Hegseth’s concern – though for very different reasons.

He disliked facial hair on himself and on others, including his soldiers. To Washington, a beard made a man look unkempt and slovenly, masking the higher emotions that civility required.

Beards were not signs of virility but of disorder. In his words, they made a man “unsoldierlike.” Every soldier, he insisted, must appear in public “as decent as his circumstances will permit.” Each was required to have “his beard shaved – hair combed – face washed – and cloaths put on in the best manner in his power.”

For Washington, this was no trivial matter. Outward appearance reflected inner discipline. He believed that a well-ordered body produced a well-ordered mind.

To him, neatness was the visible expression of self-command, the foundation of every other virtue a soldier and leader should possess.

That is why he equated beards and other forms of unkemptness with “indecency.” His lifelong battle was against indecency in all its forms. “Indecency,” he once wrote, was “utterly inconsistent with that delicacy of character, which an officer ought under every circumstance to preserve.”

More statesman than warrior

By “delicacy,” Washington meant modesty, tact and self-awareness – the poise that set genuine leaders apart from individuals governed by passions.

For him, a soldier’s first victory was always over himself.

“A man attentive to his duty,” he wrote, “feels something within him that tells him the first measure is dictated by that prudence which ought to govern all men who commits a trust to another.”

In other words, Washington became a soldier not because he was hotheaded or drawn to the thrill of combat, but because he saw soldiering as the highest exercise of discipline, patience and composure. His “warrior ethos” was moral before it was martial.

Washington’s ideal military leader was more statesman than warrior. He believed that military power must be exercised under moral constraint, within the bounds of public accountability, and always with an eye to preserving liberty rather than winning personal glory.

In his mind, the army was not a caste apart but an instrument of the republic – an arena in which self-command and civic virtue were tested. Later generations would call him the model of the “republican general”: a commander whose authority rested not on bluster or bravado but on composure, prudence and restraint.

That vision was the opposite of the one Pete Hegseth performed at Quantico.

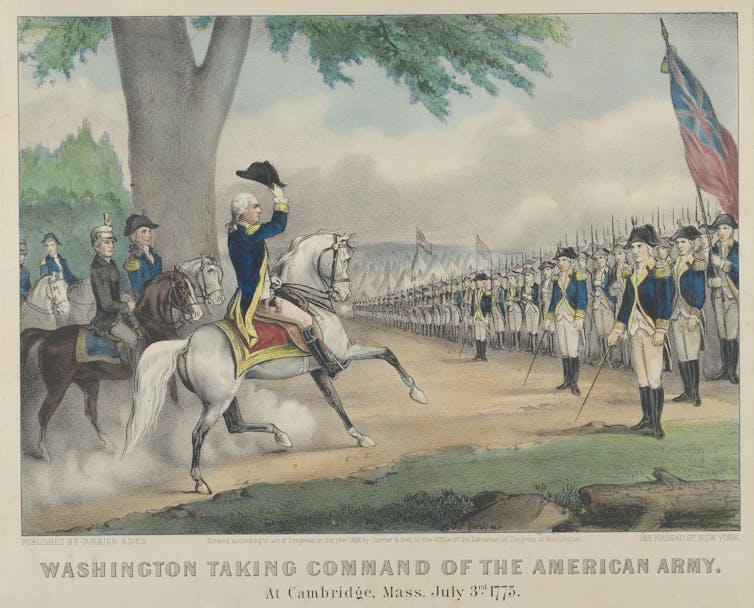

Washington formally taking command of the Continental Army on July 3, 1775, in Cambridge, Mass.Currier and Ives image, photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Washington formally taking command of the Continental Army on July 3, 1775, in Cambridge, Mass.Currier and Ives image, photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty ImagesDiscipline and steadiness, not fury and bravado

The “warrior ethos” Hegseth celebrates – loud, performative – was precisely what Washington believed a soldier must overcome.

In March 1778, after Marquis de Lafayette abandoned an impossible winter expedition to Canada, Washington praised caution over juvenile bravado.

“Every one will applaud your prudence in renouncing a project in which you would vainly have attempted physical impossibilities,” he wrote from the snows of Valley Forge.

For Washington, valor was never the same as recklessness. Success, he believed, depended on foresight, not fury, and certainly not bravado.

The first commander in chief cared little for waistlines or whiskers, in the end; what concerned him was discipline of the mind. What counted was not the cut of a man’s figure but the steadiness of his judgment.

Washington’s own “warrior ethos” was grounded in decency, temperance and the capacity to act with courage without surrendering to rage. That ideal built an army – and in time, a republic.

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Maurizio Valsania, Professor of American History, Università di Torino