George Plimpton’s 1966 nonfiction classic ‘Paper Lion’ revealed the bruising truths of Detroit Lions training camp

- Written by Stephen Siff, Associate Professor of Journalism, Miami University

Green Bay Packers wide receiver Romeo Doubs (87) and Detroit Lions cornerback Terrion Arnold (6) show off their athleticism on Sept. 7, 2025.AP Photo/Matt Ludtke

Green Bay Packers wide receiver Romeo Doubs (87) and Detroit Lions cornerback Terrion Arnold (6) show off their athleticism on Sept. 7, 2025.AP Photo/Matt LudtkeAs the Detroit Lions barrel toward a Thanksgiving Day game with the Green Bay Packers, some die-hard fans may be fantasizing about what it would be like to be on the field themselves: calling plays from the Lions huddle, accepting the snap from between a crouching center’s thighs, and spinning to hand off the football before the defensive linemen come crashing down.

In 1963, Lions head coach George Wilson allowed writer and Paris Review editor George Plimpton to enact that fantasy.

With a Sports Illustrated contract in hand, Plimpton convinced Lions management to allow him to enter preseason training camp at Cranbrook, the private boys school in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. His plan was to go undercover as a rookie quarterback for a magazine article that would reach dramatic culmination when he called a series of plays in a game of professional football.

No one expected the amateur athlete to survive for long on a field with real-life Lions. But in writing about the experience, Plimpton turned off-field fandom and on-field bumbling into literary gold.

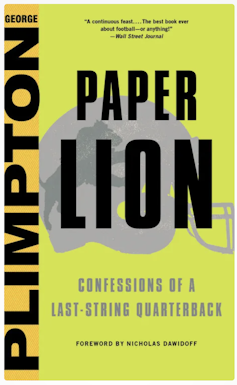

Little, Brown reissued Paper Lion in 2016.Little, Brown

Little, Brown reissued Paper Lion in 2016.Little, BrownHis resulting 1966 book, “Paper Lion: Confessions of a Last-String Quarterback,” became a bestseller that was praised by The New York Times as “one of the greatest books written on sports, and the most thoroughly engaging book on any subject in recent memory.”

A 1968 movie based on the book starred Alan Alda as Plimpton and members of the 1967 Lions team as themselves.

Decades before I became a journalism professor at Miami University of Ohio, I discovered Plimpton’s sportswriting from reading the paperback versions I found on my parents’ bookshelves. Plimpton was a leading member of a mid-20th-century class of literary journalists, including Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Gay Talese and Norman Mailer, who were becoming known for applying novelistic techniques and sometimes personal, subjective perspectives to nonfiction.

While the other literati tackled heavy topics, Plimpton’s engaging, conversational prose goofed around on the fringes of pro sports. Many of his books followed the same “participatory journalism” formula. He wrote about pitching against MLB all-stars, traveling with the PGA tour, boxing a bout against Archie Moore and playing with the Boston Bruins.

Those were just the full-length books. Other television and magazine projects had Plimpton competing in tennis and bridge; performing stand-up comedy; acting in a Western; playing with the New York Philharmonic; and attempting to be an aerialist with the circus.

However, he is best known for trying his hand quarterbacking for the Lions.

Posh writer meets the gridiron

In some ways, Plimpton seemed exactly the wrong person for this job. The possessor of a distinctively old money accent and patrician wealth and manners, he was founding editor of The Paris Review and in 1967 a mainstay of literary salons in Paris and New York. “Author, critic, interviewer, party-giver … friend of everybody, gifted, personable, energetic, bright, with-it, rich, a legend in his own time,” The New York Times gushed.

Just the kind of person whom your average football fan might enjoy seeing knocked flat.

American journalist and literary critic George Plimpton was no fan of pain, and that limited his ability on the football field.Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

American journalist and literary critic George Plimpton was no fan of pain, and that limited his ability on the football field.Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesPlimpton joined a team he described as recovering from scandal. After ending the 1962 season with an 11-3 record and a Playoff Bowl victory for third place in the NFL, the NFL commissioner’s office fined six Lions for gambling on the championship game between Green Bay and New York. More significant on field, the commissioner suspended Lions great defensive tackle and future Pro Football Hall of Famer Alex Karras for one year. Without him, the Lions would end the 1963 season 5-8-1.

Plimpton wrote his way onto the team by promising to “just hang around on the periphery of things and not bother anyone, just try to participate enough to get the feel of things.”

Wilson agreed, and Plimpton arrived at training camp a few months later with his own football, purchased from an army-navy store in Times Square, and a “mild fiction” about having played quarterback at Harvard and for the nonexistent Newfoundland Newfs.

Plimpton’s attempt at deception might raise ethical questions; however, the joke is always on him. The coaching staff seemed to have thought it would be hilarious if anyone on the team actually took the gangly 36-year-old with the nasal accent as a professional football player. It seems unlikely that anyone did.

“I never had the temerity to pretend I was something that I wasn’t,” Plimpton wrote. “The team caught on quickly enough.”

At camp, Plimpton hung around the dining hall and sat in the back of team meetings. A master of small talk, he lets the reader eavesdrop on conversations with Hall of Famers Karras, Dick “Night Train” Lane and Joe Schmidt.

Plimpton takes us with him one night to a bar frequented by coaches, where we listen in rounds of liars’ poker with Wilson, Scooter McLean and Les Bingaman. We tag along as he chats with Karras at Lindell’s A.C., the bar the player owned in downtown Detroit at the time.

Lessons in grit

At training camp, Plimpton faced the teasing of players but earned respect by facing the brutality of sport and by persisting despite the inevitability of pain. He never played football in school, beyond a beery game between Harvard Crimson and Harvard Lampoon, and did not know the basics of playing quarterback.

Several days into camp, he was allowed to participate in a play where, as quarterback, he was supposed to quickly hand off the ball to another player.

“At ‘two’ the snap back came,” Plimpton wrote. “I began to turn without the proper grip on the ball, moving too nervously, and I fumbled the ball, gaping at it, mouth ajar, as it fell and bounced twice, once away from me, then back, and rocked back and forth gaily at my feet. I flung myself on it (…) and I heard the sharp strange whack of gear, the grunts, and then a quick sudden weight whooshed the air out of me.”

The same thing happened when Plimpton was allowed to take the field in an annual intra-squad game played in Pontiac. Over his first three plays he lost 20 yards by falling down, getting knocked over by his own teammates and being literally picked from the ground by a zealous defender. On the bus ride home, Plimpton admitted to Wilson that he didn’t like being hit.

The coach gently explained that “love of physical contact” was necessary to make it in pro football.

“When kids, out in a park, chose of sides for tackle rather than touch, the guys that want to be ends and go out for the passes, or even quarterback, because they think subconsciously they can get rid of the ball before being hit, those guys don’t end up as football players,” Wilson mused. “They become great tennis players, or skiers, or high jumpers. It doesn’t mean they lack courage or competitiveness.”

“But the guys who put up their hands to be tackles or guards, or fullbacks who run not for daylight but for trouble – those are the ones who will make it as football players.”

This quality of great football players – an irrational enthusiasm for bruising physical contact – is celebrated by Plimpton in the veteran Lions who take him into their orbit. He becomes friends with Karras and offensive lineman John Gordy, in particular, and shoots the breeze on topics ranging from the NFL commissioner to Adolf Hitler.

In a subsequent book, Plimpton goes with the pair to a madcap golf tournament and starts a ridiculous business venture, suggesting the on-field madness necessary to succeed in football bleeds into off-field life as well.

But it is not Plimpton’s way to delve into the psychology of his idols. Rather, he listens as they spin tales that show how reckless the grown men who run toward trouble really are.

Stephen Siff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Stephen Siff, Associate Professor of Journalism, Miami University