Sixth year of drought in Texas and Oklahoma leaves ranchers bracing for another harsh summer

- Written by Joel Lisonbee, Senior Associate Scientist, Cooperative Institute for Research in the Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder

Cattle auctions aren’t often all-night affairs. But in Texas Lake Country in June 2022, ranchers facing dwindling water supplies and dried out pastures amid a worsening drought sold off more than 4,000 animals in an auction that lasted nearly 24 hours – about 200 cows an hour.

It was the height of a drought that has gripped the Southern Plains for the past six years – a drought that is still holding on in much of the region in 2026.

The drought cost the agriculture industry across Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas an estimated US$23.6 billion in lost crops, higher feed costs and selling off cattle from 2020 through 2024 alone. As rangeland dried out, it also fueled devastating wildfires.

Historically, droughts of this magnitude happen in the Southern Plains about once a decade, but the severe droughts of this century have been lasting longer, leaving water supplies, native rangelands and farms with little time to recover before the next one hits.

Many cattle producers and rangelands were still recovering from a severe 2010-2015 drought when a flash drought hit western Texas in spring 2020, marking the beginning of the current multibillion-dollar, multiyear and multistate drought. Ample spring rainfall in 2025 and severe flooding in central Texas that year weren’t enough to end the drought, and a powerful winter storm in late January 2026 missed the driest parts of the region.

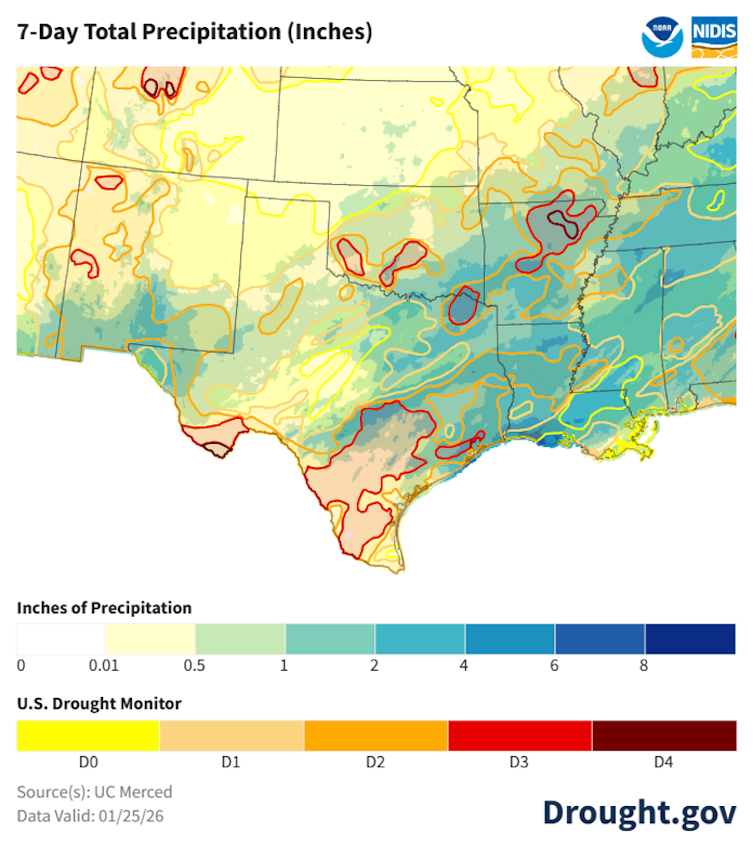

Precipitation from a severe winter storm in late January 2026, shown in blue and measured in inches, largely missed the areas with the worst drought conditions, indicated by red contour lines.UC Merced, NDMC

Precipitation from a severe winter storm in late January 2026, shown in blue and measured in inches, largely missed the areas with the worst drought conditions, indicated by red contour lines.UC Merced, NDMCIn a recent study with colleagues at the Southern Regional Climate Center and the National Integrated Drought Information System, we assessed the causes and damage from the ongoing drought in the Southern Plains.

We found three key reasons for the enduring drought and its damage: rising temperatures and a La Niña climate pattern; water supply shortages; and lingering economic impacts from the previous drought.

Weather and climate helped drive the drought

The Southern Plains is known to be a hot spot for rapid drought development, and the ongoing drought that started in 2020 is no exception.

Documented “flash droughts” – defined as periods of rapid drought onset or intensification of existing droughts – occurred at least five times in the region from 2020 to 2025. As global temperatures rise and climates warm, research warns that the frequency and severity of flash drought events will increase.

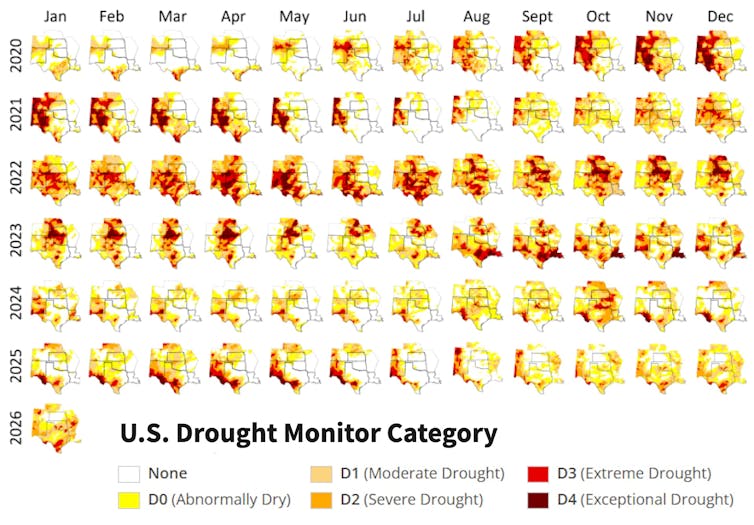

The U.S. Drought Monitor’s monthly updates from January 2020 through January 2026 show how drought moved around in the Southern Plains over those years but never let go. Darker colors reflect the intensity of drought in each location.Joel Lisonbee; compiled from U.S. Drought Monitor

The U.S. Drought Monitor’s monthly updates from January 2020 through January 2026 show how drought moved around in the Southern Plains over those years but never let go. Darker colors reflect the intensity of drought in each location.Joel Lisonbee; compiled from U.S. Drought MonitorFor the southern part of the Southern Plains, winter precipitation is closely linked to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, a climate pattern that affects weather around the world. Five of the past six years exhibited a La Niña pattern, which typically means the region sees winters that are warmer and drier than normal.

La Niña was likely the primary driver – although not the only driver – of the drought for Texas and southwest Oklahoma, and one of the reasons drought conditions have continued into 2026.

The Southern Plains have a long history with severe droughts. The Dust Bowl of the early 1930s may be the best-known example. But a history with drought doesn’t make it any easier to manage when crops and water supplies dry up.

Deeply rooted water shortages

The heat and dryness since 2020 have left many of the region’s rivers, reservoirs and even groundwater reserves well below average.

San Antonio’s reservoirs all reached record-low levels in 2024 and 2025, as did the Edwards Aquifer, which provides water for roughly 2.5 million people. They were still low as 2026 began. Surface water and groundwater resources across central and western Texas have been depleted to the point that even a few big storms can’t replenish them.

A few major rivers flow into the Southern Plains from other drought-affected regions. Consider the Rio Grande, which begins in Colorado and winds through New Mexico and along Texas’ southern border: Not only has the Lower Rio Grande valley in southern Texas missed out on needed precipitation this winter, so did the Rio Grande headwaters in southern Colorado.

Colorado is facing a snow drought in winter 2026, as is much of the western U.S. If it continues, there will be less snowmelt come summer to feed rivers, such as the Rio Grande, or fill reservoirs. In early February, the Elephant Butte, Amistad and Falcon reservoirs, along the Rio Grande, were only 11%, 34%, and 20% full, respectively.

Lingering economic impacts

Like water supplies, the economy doesn’t just recover when the rains return.

One of the reasons the current drought has been so costly is that parts of the region had not fully recovered from the 2010-2015 drought when the latest one began in 2020. With only a five-year break between droughts, the landscape behaved like someone with an already weakened immune system who caught a cold.

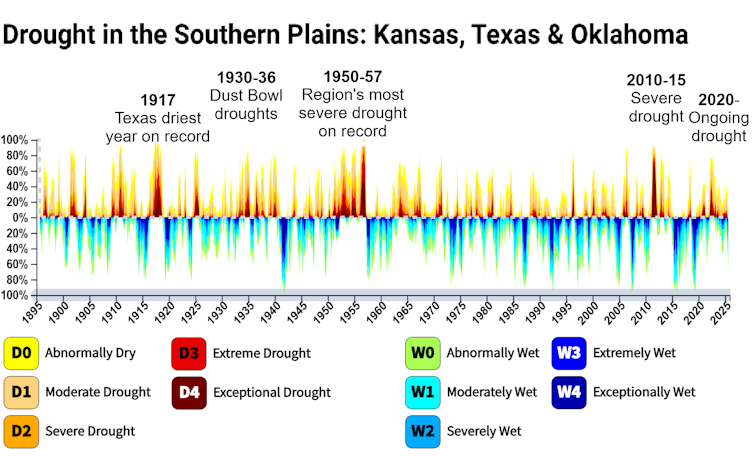

The percentage of land in different levels of drought or wetness for each month based on the nine-month Standardized Precipitation Index leading up to the selected date. Reds indicate drier conditions; blues indicate wetter conditions.National Integrated Drought Information System, NOAA Drought.gov

The percentage of land in different levels of drought or wetness for each month based on the nine-month Standardized Precipitation Index leading up to the selected date. Reds indicate drier conditions; blues indicate wetter conditions.National Integrated Drought Information System, NOAA Drought.govDuring the 2010-2015 drought, cattle producers in Texas sold off about 20% of the statewide herd as water became scarce and rangeland dried up. Rebuilding a herd after a drought is a slow process. Pasture recovery can take a year or more, and a newborn heifer will take two years to mature and produce her own first calf.

Cattle herds had still not returned to pre-2010 levels when the 2022 drought peak forced another mass sell-off. From 2020 through 2024, Texas’s herd size declined from 13.1 million to 12 million; Oklahoma’s declined from 5.3 million to 4.7 million; and Kansas’ declined from 6.5 million to 6.15 million.

Looking beyond livestock, a large percentage of the Southern Plains’ crops failed in 2022, the peak year of the drought. In Texas, 25% of the corn crop was planted but never harvested, and 45% of the soybean crop was similarly abandoned. A normal season would have yielded a $2.4 billion cotton crop in Texas, but 74% of that crop was abandoned, slashing its value to roughly $640 million.

Ending the Southern Plains drought

Is the end in sight? With La Niña fading in early 2026 and its opposite, El Niño, potentially on the horizon, there’s a chance for wetter conditions that could reduce the drought in the fall and winter months of 2026.

But the Southern Plains still have to get through spring and summer first. Ending a drought like this requires consistent precipitation over several months, and drought conditions are likely to get worse before they get better.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Joel Lisonbee, Senior Associate Scientist, Cooperative Institute for Research in the Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder