Philly’s forgotten history as a hub of anarchism with a thriving radical Yiddish press

- Written by Geoffrey Baym, Professor of Media Studies and Production, Temple University

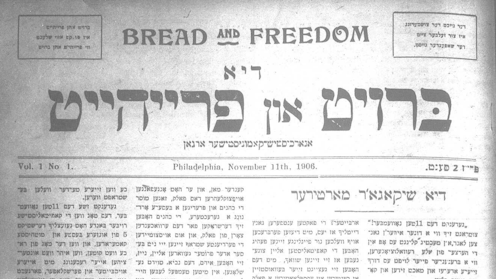

The first edition of Bread and Freedom came out on Nov. 11, 1906.From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of Broyt un Frayheyt (Bread and Freedom)

The first edition of Bread and Freedom came out on Nov. 11, 1906.From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of Broyt un Frayheyt (Bread and Freedom)On a late summer day in 1906, a small group of newly arrived Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia took a streetcar across town to Fairmount Park. Several miles from the cramped row houses and oppressive sweatshops of the immigrant quarter of South Philly, the neighborhood now known as Queen Village, they enjoyed a sunny picnic.

They weren’t there to make small talk, though.

Instead, they wanted to write “revolutionary articles” that would spark the “struggle against all that degrades and oppresses humanity,” as one of the leaders of the group, Joseph Cohen, later wrote in his 1945 memoir.

More specifically, the picnicgoers wanted to start a newspaper. It would be titled Broyt un Frayheyt – Yiddish for Bread and Freedom – the anarchist reminder that to live the good life, one needs both.

I’m a professor of media and politics at Temple University in Philadelphia. For the past year I’ve been tracking the life and times of my great-grandfather Max, a radical Yiddish journalist in the early years of the 20th century.

To my surprise, I found he had lived here in Philadelphia, and his story is part of a largely forgotten moment in U.S. history: when Philly was an epicenter of the national anarchist movement, heartily supported by the city’s burgeoning Jewish immigrant community.

Beyond the Russian pale

By 1906, thousands of people like Max had made their way to Philadelphia from the Russian “pale” – the only part of the Russian Empire where they could legally reside. They fled economic isolation and state-sanctioned persecution in search of a more stable life.

South Philly was better than where they had come from, but immigrant life then, as now, was by no means easy. They had escaped a legal regime of oppression and the perpetual threat of antisemitic mob violence. But in turn they found a world of dark alleys and dead ends. Their labor was exploited, their living conditions meager.

For some, the American promise of freedom and prosperity seemed to ring hollow.

They did, however, find one freedom they had not experienced before. They were able to speak, write and publish their ideas no matter how outlandish or against the grain.

And they could do so in Yiddish, the vernacular of daily life but a language of exile – one that in the old world had often been outlawed in print.

The Yiddish press in the United States was experiencing extraordinary growth at the time. In New York, Philadelphia and other cities, newspapers quickly emerged – and often disappeared – month over month.

Jewish anarchists in America

Max moved to Philadelphia in 1906 to work with another immigrant named Joseph Cohen. Cohen had arrived in Philadelphia three years earlier. He earned a scant living making cigars, but his real work was advocating anarchism.

At the dawn of the 20th century, anarchism was not the nihilistic chaos the term may bring to mind today. It was a heartfelt dream of a free and egalitarian society.

The anarchists believed that man-made hierarchies – political, economic and religious – were illegitimate and limited the full expression of humanity. They rejected the authority of the state. That particularly appealed to many Jewish immigrants, for whom laws in the old country had long served as vehicles of oppression.

Cohen had studied this philosophy of local autonomy and communal life with the Philadelphia activist Voltairine de Cleyre.

History may remember Emma Goldman, a Lithuanian-born New Yorker and perhaps the leading voice of American anarchism from that era. But de Cleyre was the heart and soul of Philadelphia’s anarchist scene.

Goldman once described de Cleyre as a “poet-rebel,” a “liberty-loving artist” and “the greatest woman anarchist of America.”

Voltairine de Cleyre in Philadelphia circa 1901.Wikimedia Commons

Voltairine de Cleyre in Philadelphia circa 1901.Wikimedia CommonsA tireless critic of the inequities of the industrial age, de Cleyre had taught herself Yiddish to better serve as “the apostle of anarchism” in the Jewish ghetto.

While de Cleyre could often be found speaking in front of city hall, Max, Cohen and their colleagues were more likely to gather at the corner of Fifth and South streets, the hub of Philadelphia’s Yiddish press and its culture of rambunctious street debate.

By 1906, Cohen had co-founded the anarchist Radical Library in the upstairs rooms at 229 Pine St. This provided the Philadelphia anarchists a meeting space and reading room.

But “the Jewish newspaper men, the radicals and the tireless talkers,” as the Philadelphia historian Harry Boonin wrote, still congregated in the ramshackle cafes lining the 600 block of South Fifth, where they would argue over anarchism and atheism deep into the night.

Competition with NYC comrades

Cohen’s goal was to publish a nationally influential anarchist paper that would give voice to the “comrades from Philadelphia.”

That meant direct competition with the New York Yiddish press and the influential weekly newspaper Freie Arbeiter Stimme, or The Free Voice of Labor. Edited by Saul Yanovksy on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, FAS was the center of the Jewish anarchist movement and of the Yiddish intelligentsia more broadly.

“To be able to say ‘I have written for Yanovsky,’” wrote the sociologist Robert Park in 1922, “is a literary passport for a Yiddish writer.”

Freie Arbeiter Stimme (The Free Voice of Labor) was the intellectual center of the Jewish anarchist movement at the turn of the 20th century.From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of Freie Arbeiter Stimme (The Free Voice of Labor)

Freie Arbeiter Stimme (The Free Voice of Labor) was the intellectual center of the Jewish anarchist movement at the turn of the 20th century.From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of Freie Arbeiter Stimme (The Free Voice of Labor)Although the FAS masthead said the paper was located in New York and Philadelphia, Yanovksy controlled the operation from New York, much to Cohen’s dismay.

The Philadelphia anarchists were also routinely disappointed in Yanovsky’s politics. He was too moderate for their tastes. Yanovsky favored organizing labor and voting in elections, while the Bread and Freedom group, according to Cohen, wanted to cultivate “the militancy and fighting spirit which our young comrades brought with them from cold Russia.” They advocated for more aggressive measures to counter “the submissive indifference of the bourgeoisie and the slavish patience of the workers.”

Cohen had partnered with Yanovsky earlier in 1906 to publish a daily anarchist newspaper. He maintained a small office in the back of Finkler’s cigar store at Fifth and Bainbridge streets. But the paper was printed in New York and delivered back to Philadelphia each morning by courier train.

Cohen wrote in his memoir that he suspected Yanovsky intentionally sabotaged the effort by insisting that he personally write the daily editorial, but then turning in his copy too late for the paper to make the train. After two months the partnership, and the paper, fell apart.

For Cohen, the lesson was that to be the genuine voice of the anarchist movement, he had to print the paper locally in Philadelphia.

A digest of anarchist argument

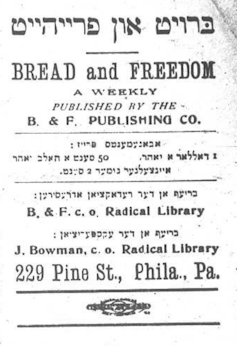

Editions of the Bread and Freedom anarchist weekly list the Radical Library at 229 Pine St. as its headquarters.From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of Bread and Freedom

Editions of the Bread and Freedom anarchist weekly list the Radical Library at 229 Pine St. as its headquarters.From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of Bread and FreedomBread and Freedom published its first issue on Nov. 11, 1906. The date was symbolic. It was the anniversary of the execution of the “Chicago martyrs” – the four men wrongly sentenced to death for the 1886 bombing at a labor rally at Chicago’s Haymarket Square. The Haymarket affair galvanized the anarchist movement among immigrants, even as it accelerated the wider fear of foreign-born radicalism.

Over the next three months, the newspaper offered a weekly digest of anarchist arguments. It translated into Yiddish Voltairine de Cleyre’s critique of capitalism and what she called its “moral bankruptcy” – its hunger for wealth, power and material possessions. It attacked what de Cleyre called the “dominant idea” of the times – “the shameless, merciless” exploitation of the worker, “only to produce heaps and heaps of things – things ugly, things harmful, things useless, and at the best largely unnecessary.”

In the strongest of terms – “bombastic,” in the words of one local historian – the paper echoed de Cleyre’s call for the “restless, active, rebel souls” of immigrant Philadelphia to rise up to oppose the “great and lamentable error” of industrial capitalism.

Almost as soon as it began, however, Bread and Freedom ran out of money. Its rhetoric was exciting but ineffective. The paper offered no real solutions beyond an impossible demand to dismantle the capitalist state.

Although two members of the group were briefly detained by the police in Baltimore for selling a radical newspaper, their fiery propaganda lit no revolutionary spark.

Instead, it disappeared quietly, folding in January 1907.

Shifting tactics

Even then, a different kind of immigrant was arriving in the U.S. from Russia. Their radical politics were coupled with organizational acumen.

Many of the older anarchists would join forces with these newcomers, and the effort morphed into something more pragmatic. They helped build the foundations of the 20th-century labor movement, which successfully fought for once-radical ideals such as the eight-hour workday and paid sick leave.

Cohen moved to New York and took over as editor of FAS in 1923. That was a tense period for the Jewish left, following the Russian revolution of 1917 and the Communist rise to power. In response, the U.S. government suppressed domestic radicalism, arresting and at times deporting foreign-born leftists, and anarchism fell out of favor.

A few years earlier, though, the streets of South Philly had been home to a vibrant space of free speech and boundless political imagination. It would not last long, but it is a moment I believe is worth remembering.

Geoffrey Baym does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Geoffrey Baym, Professor of Media Studies and Production, Temple University