Malaysia confronts the realities of MAGA diplomacy and Trump’s brash ambassadorial pick

- Written by Meredith Weiss, Professor of Political Science, University at Albany, State University of New York

Donald Trump's nomination of right-wing influencer Nick Adams as U.S. ambassador to Malaysia has not gone over well in Kuala Lumpur.Mohd Rasfan/AFP via Getty Images

Donald Trump's nomination of right-wing influencer Nick Adams as U.S. ambassador to Malaysia has not gone over well in Kuala Lumpur.Mohd Rasfan/AFP via Getty ImagesPresident Donald Trump’s pick to be the United States’ next ambassador to Malaysia has raised more than a few eyebrows in the Southeast Asian nation. Right-wing influencer Nick Adams, a naturalized American born and raised in Australia, is, by his own account, a weightlifting, Bible-reading, “wildly successful” and “extremely charismatic” fan of Hooters and rare steaks, with the “physique of a Greek God” and “an IQ over 180.”

Such brashness seems at odds with the usually more quiet business of diplomacy. The same could be said about Adams’ lack of relevant experience, temperament and expressed opinions – which clash starkly with prevailing sentiment in majority-Muslim, socially conservative Malaysia.

Whereas the U.S. usually sends a career State Department official as ambassador to Malaysia, Adams is most definitely a “political” nominee. His prior public service, as councilor, then deputy mayor, of a Sydney suburb ended abruptly in 2009 amid displays of undiplomatic temper. Yet far more problematic for his new posting is his past perceived disparaging of Islam and ardent pro-Israel views – lightning rod issues in a country that lacks diplomatic relations with Israel and whose population trends strongly pro-Palestinian.

So it was little surprise when news of Adam’s nomination on July 9, 2025, prompted angry pushback among the Malaysian public and politicians.

Whether or not Malaysia would officially reject his appointment, assuming Adams is confirmed, remains uncertain, notwithstanding strong domestic pressure on Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim to do so.

But regardless, the nomination marks a turning point in U.S.-Malaysian diplomatic relations, something I have been tracking for over 25 years. In my view, it communicates an overt U.S. disregard for diplomatic norms, such as the signaling of respect and consideration for a partner state. It also reflects the decline in a relationship that for decades had been overwhelmingly stable and amicable. And all this may play into the hands of China, Washington’s main rival for influence in Southeast Asia.

Trump wedge in US–Malaysia relations

The U.S. and Malaysia have largely enjoyed warm relations over the years, notwithstanding occasional rhetorical grandstanding, especially on the part of former longtime Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.

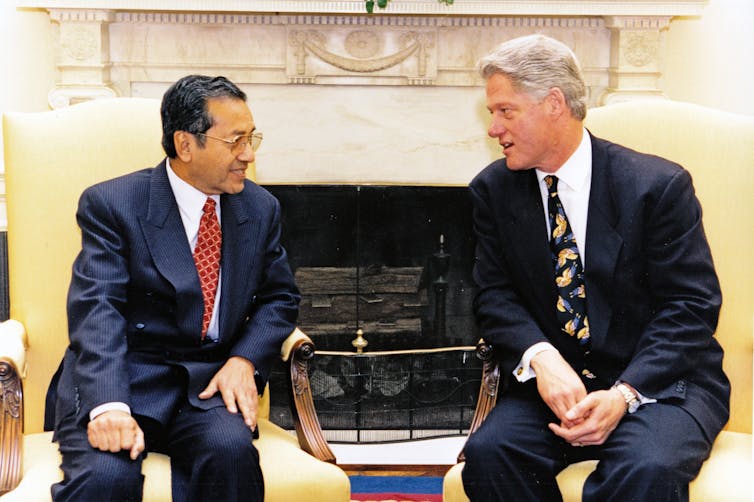

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and U.S. President Bill Clinton talk at the White House in 1996.Ralph Alswang/Consolidated News Pictures/Getty Images

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and U.S. President Bill Clinton talk at the White House in 1996.Ralph Alswang/Consolidated News Pictures/Getty ImagesHaving successfully battled a communist insurgency during the mid-20th century, Malaysia remained reliably anti-communist throughout the Cold War, much to Washington’s liking. Malaysia also occupies a strategically important position along the Strait of Malacca and has been an important source of both raw materials such as rubber and for the manufacturing of everything from latex gloves to semiconductors.

In return, Malaysia has benefited both from the U.S. security umbrella and robust trade and investment.

But even before Trump’s announcement of his ambassadorship pick, bilateral relations were tense.

The most immediate cause was tariffs. In April, the U.S. announced a tariff rate for Malaysia of 24%. Despite efforts to negotiate, the Trump administration indicated the rate would increase further to 25% should no deal materialize by Aug. 1. That the White House released its revised tariff rate just two days before announcing Adams’ nomination – and just over a month after Ibrahim held apparently cordial discussions with U.S. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore – only added to Malaysia’s grievance.

Malaysia may reap some benefit from the new U.S. trade policy, should Trump’s broader agenda results in supply chains bypassing China in favor of Southeast Asia, and investors seek new outlets amid Trump’s targeted feuds. But Malaysia’s roughly US$25 billion trade surplus with the U.S., its preference for “low-profile functionality” in regard to its relationship with the U.S., and the general volatility of economic conditions, leave Malaysia still vulnerable.

Moreover, trade policy sticking points for the U.S. include areas where Malaysia is loath to bend, such as in its convoluted regulations for halal certification and preferential policies favoring the Malay majority that have long hindered trade negotiations between the two countries.

End of the student pipeline?

The punishing tariffs the White House has threatened leave Malaysia in a bind. The U.S. is Malaysia’s biggest investor and lags only China and Singapore in volume of trade. As such, the government in Kuala Lumpur may have little choice but to sacrifice domestic approval to economic expediency.

Nor is trade the only source of angst. The White House’s pressure on American institutions of higher education is effecting collateral damage on a host of its ostensible allies, Malaysia included. Although numbers have declined since the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, the U.S. has remained a popular destination for Malaysians seeking education abroad.

In the 1980s, over 10,000 Malaysians enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities annually. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, numbers stabilized at around 8,000. But after, enrollments struggled to recover – reaching only 5,223 in 2024. Now, they are falling anew.

In the first Trump administration, the visa approval rate for Malaysian students remained high despite Trump’s “Muslim ban” exacerbating impressions of an unwelcoming environment or difficult process.

Now, economic uncertainty from trade wars and a struggling Malaysian currency, coupled with proliferating alternatives, make the comparatively high expense of studying in the U.S. even more of a deterrent.

Yet what propelled Anwar’s administration to announce that it will no longer send government-funded scholarship students to the U.S. – a key conduit for top students to pursue degrees overseas – was specifically the risks inherent in Trump’s policies, including threats to bar foreign students at certain universities and stepped-up social media screening of visa applicants.

Looking beyond a US-led order

Clearly, Malaysia’s government believes that deteriorating relations with the U.S. are not in its best interests. Yet as the junior partner in the relationship, Malaysia has limited ability to improve them.

In that, Kuala Lumpur has found itself in a similar boat to other countries in the region who are likewise reconsidering their strategic relationship with the United States amid Trump 2.0’s dramatic reconfiguration of American foreign policy priorities.

When sparring with China for influence in Southeast Asia, the U.S. has, until recently, propounded norms of a Western-centric “liberal international order” in the region – promoting such values as openness to trade and investment, secure sovereignty and respect for international law.

Malaysia has accepted, and benefited from, that framework, even as it has pushed back against U.S. positions on the Middle East and, in the past, on issues related to human rights and civil liberties.

But amid the Trump administration’s unpredictability in upholding this status quo, a small, middle-income state like Malaysia may have little option beyond pursuing a more determinedly nonaligned neutrality and strategic pragmatism.

Indeed, as the U.S. sheds its focus on such priorities as democracy and human rights, China’s proffered “community with a shared future,” emphasizing common interests and a harmonious neighborhood, cannot help but seem more appealing.

This is true even while Malaysia recognizes the limitations to China’s approach, too, and resists being pushed to “pick sides.” Malaysia is, after all, loath to be part of a sphere of influence dominated by China, especially amid ongoing antagonism over China’s claims in the South China Sea – something that drives Malaysia and fellow counterclaimants in Southeast Asia toward security cooperation with the U.S.

That said, Anwar’s administration seemed already to be drifting toward China and away from the West even before the latest unfriendly developments emanating from Washington. This includes announcing in June 2024 its plan to join the BRICS economic bloc of low- and middle-income nations.

Burning bridges

Now, the more bridges the U.S. burns, the less of a path it leaves back to the heady aspirations of the first Trump administration’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” framework, which had highlighted the mutual benefit it enjoyed and shared principles it held with allies in Asia.

Instead, Malaysia’s plight exemplifies what a baldly transactional and one-sided approach produces in practice.

As one ruling-coalition member of parliament recently described, Adams would be the rare U.S. ambassador with whom Malaysian politicians would be loath to pose for photos. And that fact alone speaks volumes about diplomacy and evolving global strategic realities in the MAGA era.

Meredith Weiss does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Meredith Weiss, Professor of Political Science, University at Albany, State University of New York