Venezuela’s oil industry has flailed under government control – Mexico and Brazil have had more success with nationalizing

- Written by Skip York, Nonresident Fellow in Energy and Global Oil, Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University

The Venezuelan state-run oil company is contending with aging infrastructure.Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post via Getty Images

The Venezuelan state-run oil company is contending with aging infrastructure.Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesU.S. President Donald Trump has ignited a contentious debate over who has the right to control Venezuela’s vast oil reserves.

Speaking on Jan. 3, 2026, after the U.S. military seized Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, the U.S. president declared, “We built Venezuela’s oil industry, and now we’re going to take it back.”

By Jan. 6, Trump was saying that Venezuela would provide the U.S. with up to 50 million barrels of oil in the near future.

The next day, the U.S. seized two tankers bound from Venezuela for other markets – less than a month after it seized two others it said were transporting Venezuelan oil.

Long-term plans go much further. Trump envisions major U.S. oil companies, such as Chevron and ExxonMobil, to invest some US$100 billion into reviving Venezuela’s struggling industry, with the investing companies reimbursed through future production. So far, neither Venezuelan authorities nor U.S. oil companies have said whether they’re willing to do this.

As a scholar of global energy, I believe that Trump’s words and actions, including his consultations with oil executives before Maduro’s removal, signal a bold push to reassert American dominance in a country with vast oil reserves.

A motorcycle passes in front of an oil-themed mural in Caracas, Venezuela, on May 9, 2022.Javier Campos/NurPhoto via Getty Images

A motorcycle passes in front of an oil-themed mural in Caracas, Venezuela, on May 9, 2022.Javier Campos/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesTrump’s rationale

Trump’s “Venezuela took our oil, we’re taking it back” rationale apparently references the South American nation’s initial nationalization of its oil industry in 1976, plus a wave of expropriations in 2007 under Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

U.S. oil companies played a big role in launching and sustaining Venezuela’s oil boom, starting in the 1910s. Companies such as Standard Oil, a predecessor of ExxonMobil, and Gulf Oil, which eventually became part of Chevron, invested heavily in exploration, drilling and infrastructure, transforming Venezuela into a major global supplier.

Contracts from that era often blurred lines between reserve ownership and production rights. Venezuela legally retained subsoil ownership but granted or sold broad concessions to foreign operators, such as Royal Dutch-Shell. That effectively gave control of reserves and production to the oil companies, but not forever.

This ambiguity likely has played a role in Trump alleging outright theft through nationalization, a claim that holds little grounding in the historical precedent of how Venezuela and other nations have managed ownership of their natural reserves.

Oil nationalization

When a country nationalizes its oil industry, control is transferred from private, often foreign-owned, companies to the government.

Nationalization can involve the outright expropriation of facilities and reserves – with or without compensation – or the renegotiation of oil production contracts. Alternatively, a government may get a bigger stake in the joint ventures it already has with foreign oil companies.

While privately owned oil companies primarily are accountable to their shareholders and focus mainly on maximizing profits, most government-run oil companies have other priorities too. These might include pumping revenue into safety net programs, domestic energy security, the development of other industries and military spending.

Sometimes those other goals take so much money out of the oil company’s orbit that they interfere with operational efficiency and reinvestment, slowing growth or even reducing production capacity. That’s what happened in Venezuela, where oil production has fallen sharply since 2002.

But other Latin American countries have also nationalized their oil industries with better results.

Mexico’s experience

In Mexico, President Lázaro Cárdenas’ 1938 expropriation of foreign oil assets – primarily from U.S. and British companies – was the region’s first such assertion of economic independence.

Amid labor disputes and perceived exploitation, 17 privately owned companies were nationalized, creating Petróleos Mexicanos as Mexico’s government-run oil monopoly. Mexicans celebrate the formation of this company, known as Pemex, every year on March 18 as a symbol of national sovereignty.

Despite initial boycotts and diplomatic strain, Mexico eventually compensated the foreign companies that lost their property. But it isolated its oil sector from international capital and technology for decades.

Due to the depletion of Pemex’s largest oilfields, chronic underinvestment, a failure to adopt new technologies and unwise policy choices, production, which peaked at 3.8 million barrels a day in 2004, began to decline. Mexico responded in 2013 and 2014 with reforms that opened the oil, gas and power generation industries to private capital.

By 2018, political backlash around a perceived loss of sovereignty and uneven benefits led to a policy reversal. Oil output continues to shrink; it now stands at 1.8 million barrels per day.

Mexico’s experience underscores how oil nationalization can foster self-reliance while hindering production.

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, left, delivers a speech on the 86th anniversary of the nationalization of oil on March 18, 2024.Rodrigo Oropeza/AFP via Getty Images

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, left, delivers a speech on the 86th anniversary of the nationalization of oil on March 18, 2024.Rodrigo Oropeza/AFP via Getty ImagesBrazil’s approach

Brazil also nationalized its oil industry in 1953, when President Getúlio Vargas established Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. as a state-owned company.

From the start, Petrobras had a monopoly over all Brazilian oil exploration and production. The government expanded the company’s scope when it nationalized all privately owned refineries by 1964.

Brazil’s oil nationalization was part of the country’s broader effort to develop its own industrial capacity and reduce its dependence on foreign oil.

Petrobras has changed significantly since its founding, especially after President Fernando Henrique Cardoso signed an oil deregulation law in 1997. It’s now a state-controlled company, in which investors may buy and sell shares. The government has forged many partnerships with private oil companies, drawing foreign investment.

This strategy succeeded. Production has quadrupled from 0.8 million barrels per day in 1997 to 3.4 million in 2024.

Shell, Total Energies, Equinor, ExxonMobil and other foreign oil companies have provided capital, technology and execution capacity, particularly with deep-water drilling.

A man walks past the headquarters of Petrobras in Rio de Janeiro in 2022.Fabio Teixeira/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A man walks past the headquarters of Petrobras in Rio de Janeiro in 2022.Fabio Teixeira/Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesVenezuela’s nationalization

Venezuela’s oil nationalization, by contrast, shifted from cooperation with foreign oil companies to confrontation with them.

President Carlos Andrés Pérez first nationalized Venezuela’s oil industry in 1976, creating Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. Foreign companies received compensation of about 25% for losing their assets. Many transitioned into service providers or formed joint ventures with the new company, PDVSA.

Venezuela made its oil sector more open to foreign capital in the 1990s. It aimed at the time to boost output and develop the Orinoco Belt in eastern Venezuela, which has some of the world’s biggest oil reserves.

This policy contributed to Venezuelan production reaching a historical peak of more than 3 million barrels per day in 2002.

Chávez changes everything

Hugo Chávez, elected president of Venezuela in 1998, reversed course.

In 2003, after a strike briefly but severely slashed national output, Chávez consolidated control over the oil industry. He purged PDVSA of his critics, replacing managers who had expertise with his political allies, and fired over 18,000 employees.

Venezuela expropriated operating assets, converted contracts held by private companies into PDVSA-controlled joint ventures and made sharp and unpredictable increases in the taxes and royalties foreign oil companies had to pay.

Foreign oil companies suffered from chronic payment delays, along with restrictive foreign exchange rules and new laws that weakened contract enforcement and made it harder for companies to use arbitration to resolve disputes.

In 2007, Chávez forced foreign oil companies partnering with PDVSA to renegotiate their agreements, leading to the partial nationalization of their stakes in those ventures.

Several foreign oil companies, including ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil, rejected the new terms of engagement and left Venezuela.

Their legal disputes with Venezuela over billions of dollars in joint venture assets and severed revenue-sharing agreements have never been resolved.

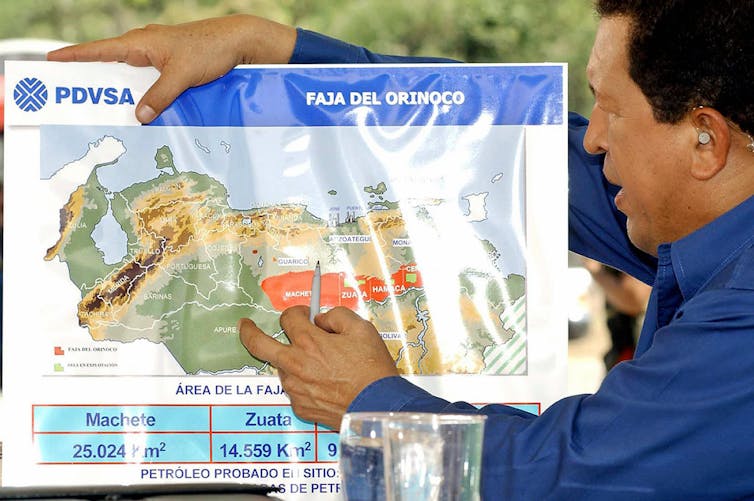

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez shows on a map the location of new oil wells operating in the country in 2004.HO/AFP via Getty Images

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez shows on a map the location of new oil wells operating in the country in 2004.HO/AFP via Getty ImagesThe Houston-headquartered company, which has had a presence in Venezuela since 1924, now plays the largest role of any foreign oil company in the country. It produces 240,000 barrels per day, about 25% of Venezuela’s total output.

The government also reclassified vast oil deposits as “proven” at a time when global oil prices were very high, rendering their exploration and production more economically viable. That change tripled this self-reported and never-verified estimate of Venezuela’s proven oil reserves to approximately 300 billion barrels.

Conditions get worse under Maduro

Venezuelan oil output further declined while Maduro served as president, falling to 665,000 barrels per day in 2021. Since then, production has recovered somewhat, rebounding to about 1.1 million barrels per day by late 2025 – about one-third of its historic high.

This overall decline is due to mismanagement, corruption and more than a decade of U.S. sanctions. Infrastructure decay – leaking pipelines, outdated refineries held together by makeshift repairs – has exacerbated this crisis.

Many hurdles are in the way of the industry’s recovery, including ongoing and potentially future legal disputes, geopolitical risks and the need for massive investments. Returning Venezuela’s oil production to its peak of 3 million barrels per day could cost more than $180 billion.

The national oil industry is hard to ignore in Venezuela.Jesus Vargas/picture alliance via Getty Images

The national oil industry is hard to ignore in Venezuela.Jesus Vargas/picture alliance via Getty ImagesBetter example

As Brazil’s experience suggests, governmental control over oil production and sales is not inherently bad for a country’s economic welfare.

Norway is an even stronger example. That oil-rich Nordic country has evaded what some scholars call the “resource curse” by treating the oil that its nationally owned company, now called Equinor, has produced as a source of lasting wealth for the Norwegian people.

Revenue from the Norwegian government’s 67% stake in Equinor has accumulated in a sovereign wealth fund worth more than $2 trillion and helped Norway diversify its economy.

As the Venezuelan government regroups following Maduro’s removal, there’s much it can learn from other countries that have managed to maintain more stability alongside state-controlled oil production.

Did prior consulting work for PdVSA in 2002-2003

Authors: Skip York, Nonresident Fellow in Energy and Global Oil, Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University