When government websites become campaign tools: Blaming the shutdown on Democrats has legal and political risks

- Written by Stephanie A. (Sam) Martin, Frank and Bethine Church Endowed Chair of Public Affairs, Boise State University

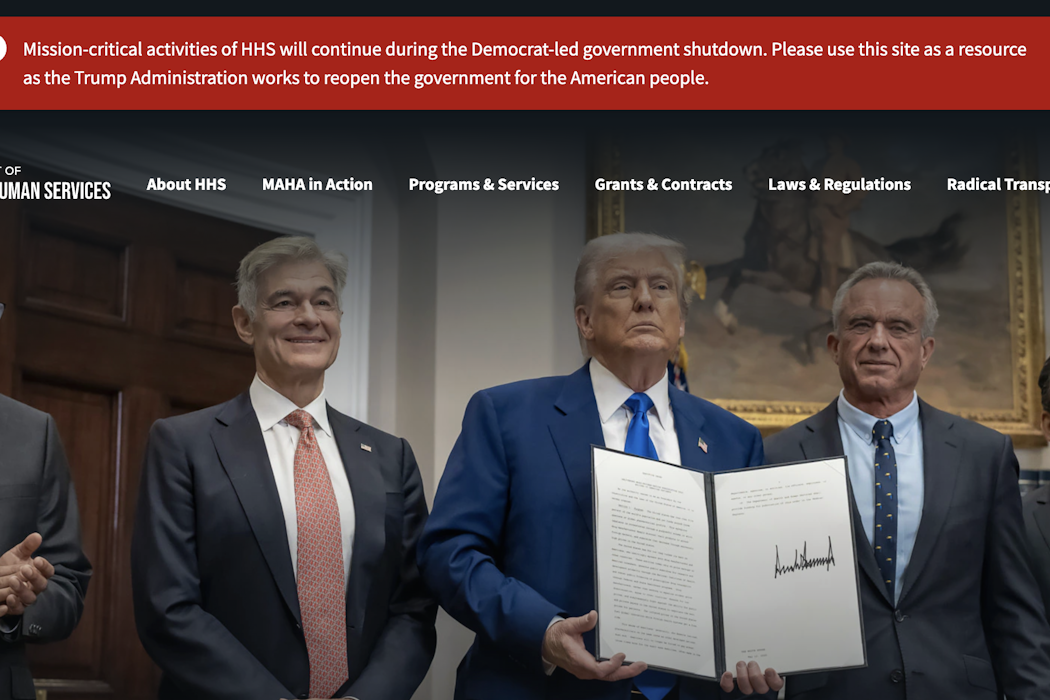

Screenshot of the Department of Health and Human Services homepage on Oct. 14, 2025.HHS website

Screenshot of the Department of Health and Human Services homepage on Oct. 14, 2025.HHS websiteFor decades, federal shutdowns have mostly been budget fights. The 2025 one has become bigger than that: It’s turned into a messaging war.

Official government communications, including website banners, out-of-office email replies and autogenerated responses that denounce “Senate Democrats,” “the Radical Left” or “Democrats’ $1.5 trillion wishlist” for closing the government, mark a sharp break from past practice.

These messages are more than rhetorical escalation. Many may violate the Hatch Act, the 1939 statute that limits partisan political activity by federal employees and agencies. They also represent new tests for how far a White House can push the bounds of campaign-style messaging while also claiming to govern.

In any democracy, power lies not only in who writes the laws or signs the budgets but in who shapes the story. Communication is not an afterthought or byproduct of governance. It is one of its essential instruments. Political narrative helps citizens understand who’s responsible, who’s acting in good faith and who’s to blame.

The 2025 shutdown has turned that truth into strategy. Federal communication systems – agency websites, automated emails and public information portals – are being used to persuade rather than inform. It’s a move that is both politically risky and legally perilous.

Serve the public, not a party

The Hatch Act was passed during the Great Depression, after years of concern that federal agencies were being used improperly as political machines. Its goal was simple: to ensure that public servants worked for the American people, not for the party in power.

At its core, the Hatch Act prohibits executive branch federal employees – except for the president and vice president – from engaging in partisan political activity as part of their official duties or under their official authority. Government workers may not use their positions or public resources to influence elections, coerce individual behavior or engage in political advocacy.

The law requires federal agencies to avoid the partisan fray and focus on serving the public rather than political agendas.

The Office of Special Counsel, which enforces the law, has been clear on this point. “The purpose of the Act,” says an Office of Special Counsel guide written for federal employees, “is to maintain a federal workforce that is free from partisan political influence or coersion.” Government communication can inform, but it cannot campaign.

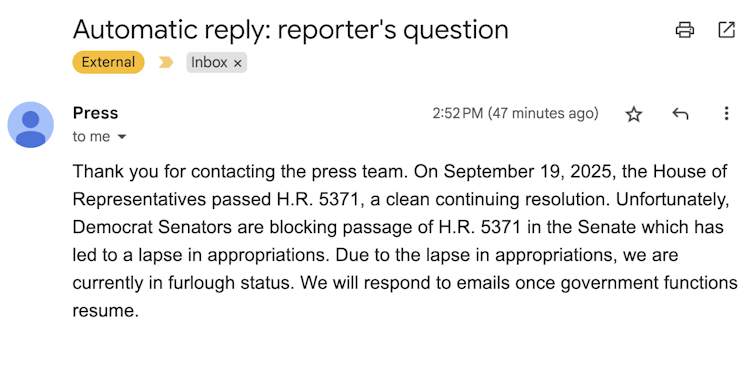

An auto-reply to an email sent to the press staff at the U.S. Department of Education on Oct. 14, 2025.CC BY

An auto-reply to an email sent to the press staff at the U.S. Department of Education on Oct. 14, 2025.CC BYYet the shutdown has already produced multiple potential violations:

• The Department of Education, according to a lawsuit, altered employees’ email auto-responses – without consent – to say things like “the Democrats have shut the government down.” Such changes do more than convey impartial information. They compel employees to align themselves with institutionally imposed scripts.

• Likewise, agencies including Health and Human Services and the Small Business Administration reportedly distributed or directed staff to adopt partisan out-of-office auto-replies assigning blame to Democrats.

• The Department of Housing and Urban Development posted a banner on its official website stating that the “Radical Left are going to shut down the government.”

Taken individually, each incident might provoke a Hatch Act complaint. Collectively, they amount to a systematic campaign to transform nonpartisan federal agencies into partisan political messengers.

The message on the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development homepage, Oct. 14, 2025.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

The message on the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development homepage, Oct. 14, 2025.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban DevelopmentWhy this is unprecedented

What sets the 2025 messaging apart isn’t just its volume – it’s the scale, the coordination and the brazenness of its political targeting.

In past shutdowns, partisan spin lived mostly in press conferences and campaign talking points. Agencies themselves, even under pressure, stayed neutral.

This time, the administration is using the machinery of government to deliver partisan blame.

The timing and similarity of messages across departments seems coordinated. Housing and Urban Development posted a banner blaming Democrats the day before the shutdown began. Within hours, other agencies followed using nearly identical language.

More troubling are the reported changes to federal employees’ auto-replies without their consent.

These missives forced career civil servants, many of them furloughed, to become unwilling messengers for partisan ends. Federal agencies and their workers are supposed to serve everyone, not only those who support the party in power.

And because the watchdogs who could enforce the legal boundary are also sidelined – the Office of Special Counsel is furloughed – complaints have nowhere to go, at least for now. They simply land in unattended email inboxes.

Legal challenges and limits

Whether shutdown communications truly violate the Hatch Act – or related laws – is not yet clear. The administration could argue that it’s not campaigning but merely explaining why services are suspended. As a scholar of political communication and American democracy, I believe that defense weakens when official messages explicitly assign partisan blame or name a political party.

And not every political statement is a Hatch Act violation. The law allows employees to express views off duty or in private contexts, so long as they use their own phones and computers.

Even if the Office of Special Counsel later finds violations, harm will likely persist. Once messages are posted or auto-replies sent, their effects can’t always be undone. And because ethics officials are furloughed, too, accountability will be delayed, if it comes at all.

Some employees are likely to claim their speech rights were violated by being forced to send partisan messages. This is an argument already at the heart of the lawsuit filed by the American Federation of Government Employees against the Education Department.

Doors at the Internal Revenue Service in a Seattle federal building are locked and a sign advises that the office will be closed during the 2018-2019 partial government shutdown.AP Photo/Elaine Thompson

Doors at the Internal Revenue Service in a Seattle federal building are locked and a sign advises that the office will be closed during the 2018-2019 partial government shutdown.AP Photo/Elaine ThompsonWhy this matters

Federal agencies exist to administer laws impartially and to do so on behalf of the people.

When the government uses its own infrastructure for partisan messaging, the very neutrality on which democratic governance depends erodes. It dilutes public trust in the idea of a neutral state.

The damage also extends into the future. If the current administration succeeds in turning its administrative machinery into a political weapon, without consequence, a precedent will be created. Future presidents may be tempted to follow suit, making acceptable the use of taxpayer-funded systems as campaign tools.

And because enforcement bodies such as the Office of Special Counsel also are sidelined during a shutdown, accountability has to wait. That creates an asymmetry of power: One side gets to amplify its message through government channels in real time, while its opponents must wait for the system to restart just to file a complaint. By the time they can, the moment will have passed and the political narrative is likely to have already hardened.

Crises demand explanation, even blame. Citizens expect their leaders to tell them what went wrong. But they also expect honesty and fairness in how that story is told. The administration’s messaging strategy during this shutdown tests whether government communication remains a public service or becomes another instrument of political power.

Stephanie A. (Sam) Martin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Stephanie A. (Sam) Martin, Frank and Bethine Church Endowed Chair of Public Affairs, Boise State University