Building a stable ‘abode of thought’: Kant’s rules for virtuous thinking

- Written by Alexander T. Englert, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Richmond

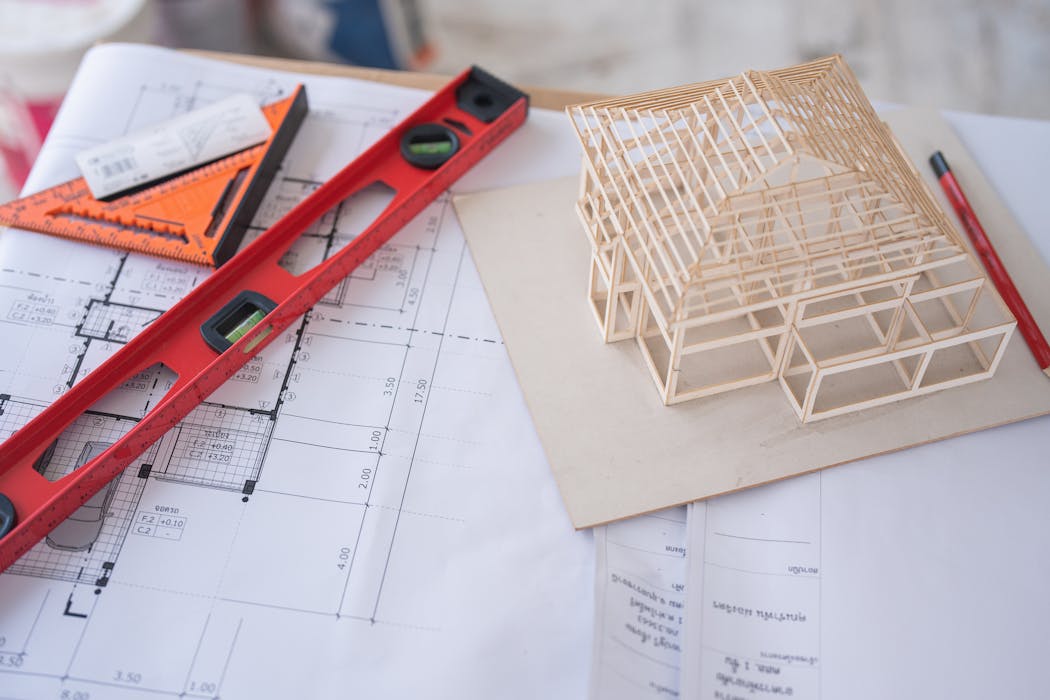

Virtuous thinking, Kant wrote, is like good carpentry: It builds strong ideas in harmony with one another. Jackyenjoyphotography/Moment via Getty Images

Virtuous thinking, Kant wrote, is like good carpentry: It builds strong ideas in harmony with one another. Jackyenjoyphotography/Moment via Getty ImagesWhat makes a life virtuous? The answer might seem simple: virtuous actions – actions that align with morality.

But life is more than doing. Frequently, we just think. We observe and spectate; meditate and contemplate. Life often unfolds in our heads.

As a philosopher, I specialize in the Enlightenment thinker Immanuel Kant, who had volumes – literally – to say about virtuous actions. What I find fascinating, however, is that Kant also believed people can think virtuously, and should.

To do so, he identified three simple rules, listed and explained in his 1790 book, “Critique of the Power of Judgment,” namely: Think for yourself. Think in the position of everyone else. And, finally, think in harmony with yourself.

If followed, he thought a “sensus communis,” or “communal sense,” could result, improving mutual understanding by helping people appreciate how their ideas relate to others’ ideas.

Given our current world, with its “post-truth” culture and isolated echo chambers, I believe Kant’s lessons in virtuous thinking offer important tools today.

Rule 1: Think for yourself

Thinking can be both active and passive. We can choose where to direct our attention and use reason to solve problems or consider why things happen. Still, we cannot completely control our stream of thought; feelings and ideas bubble up from influences outside our control.

One kind of passive thinking is letting others think for us. Such passive thinking, Kant thought, was not good for anybody. When we accept someone else’s argument without a second thought, it is like handing them the wheel to think for us. But thoughts lie at the foundation of who we are and what we do, thus we should beware of abdicating control.

A late 18th-century portrait of Immanuel Kant, possibly by Elisabeth von Stägemann.Norwegian Digital Learning Arena via Wikimedia Commons

A late 18th-century portrait of Immanuel Kant, possibly by Elisabeth von Stägemann.Norwegian Digital Learning Arena via Wikimedia CommonsKant had a word for handing over the wheel: “heteronomy,” or surrendering freedom to another authority.

For him, virtue depended on the opposite: “autonomy,” or the ability to determine our own principles of action.

The same principle holds true for thinking, Kant wrote. We have an obligation to take responsibility for our own thinking and to check its overarching validity and soundness.

In Kant’s day, he was especially concerned about superstition, since it provides consoling, oversimplified answers to life’s problems.

Today, superstition is still widespread. But many new, pernicious forms of trying to control thought now proliferate, thanks to generative artificial intelligence and the amount of time we spend online. The rise of deepfakes, the use of ChatGPT for creative tasks, and information ecosystems that block out opposing views are but a few examples.

Kant’s Rule 1 tells us to approach content and opinions cautiously. Healthy skepticism provides a buffer and leaves room for reflection. In short, active or autonomous thinking protects people from those who seek to think for them.

Rule 2: Think in the position of everyone else

Pride often tempts us to believe that we have everything figured out.

Rule 2 checks this pride. Kant recommends what philosophers call “epistemic humility,” or humility about our own knowledge.

Stepping outside our own beliefs isn’t just about opening up new perspectives. It’s also the bedrock of science, which seeks shared agreement about what is and is not true.

Suppose you’re in a meeting and a consensus is taking shape. Strong personalities and a quorum support it, but you remain unsure.

At this point, Rule 2 does not recommend that you adopt the view of the others. Quite the opposite, in fact. If you simply accept the group’s conclusion without further thought, you’d be breaking Rule 1: Think for yourself.

Instead, Rule 2 prescribes temporarily detaching yourself from even your own way of thinking, especially your own biases. It’s an opportunity to “think in the position of everyone else.” What would a fair and discerning thinker make of this situation?

Kant believed that, while difficult, a standpoint can be achieved in which biases all but vanish. We might notice things that we missed before. But this requires appreciating our own limitations and seeking a wider, more universal view.

Again, Kant’s idea of virtue depends on autonomy, so Rule 2 isn’t about letting others think for us. To be responsible for how we shape the world, we must take responsibility for our own thinking, since everything flows from that point outward.

But it emphasizes the “communal” part of the “sensus communis,” reminding us that it must be possible to share what is true.

Rule 3: Think in harmony with yourself

The final rule, Kant maintained, is both the most difficult and profound. He said that it was the task of becoming “einstimmig,” literally “of one voice” with ourselves. He also uses a related term, “konsequent” – coherent – to express the same idea.

Immanuel Kant’s tomb at the Konigsberg Cathedral in Kaliningrad, Russia.Denis Gavrilov/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Immanuel Kant’s tomb at the Konigsberg Cathedral in Kaliningrad, Russia.Denis Gavrilov/iStock via Getty Images PlusTo clarify, a metaphor that Kant employed can help – namely, carpentry.

Constructing a building is complex. The blueprint must be sound, the building materials must be high quality, and craftsmanship matters. If the nails are hammered sloppily or steps performed out of order, then the edifice might collapse.

Rule 3 tells us to construct our abode of thought with the same care as when constructing a house, such that stability between the parts results. Each thought, belief and intention is a building block. To be “einstimmig” or “bündig” – to be in “harmony” – these building blocks should fit well together and support each other.

Imagine a colleague who you believe has impeccable taste. You trust his opinions. But one day, he shares his secret obsession with death metal music – a genre you dislike.

A disharmony in thought might result. Your reaction to his love of death metal reveals a further belief: Your belief that only people with disturbed taste could love something you perceive to be so grating to the spirit. But he seems, otherwise, like such a thoughtful and pleasant person!

Rather than immediately change your belief about him, Kant’s third rule commands you to investigate the world and your own thoughts further. Perhaps you have never listened to death metal with a discerning spirit. Maybe your original beliefs about your colleague were inaccurate. Or could it be that having good taste is more complex than you originally thought?

Rule 3 leads us to do a system check of our mental architecture, whether we’re considering music, politics, morality or religion. And if that architecture is stable, Kant thinks that rewards will follow.

Sure, harmony is satisfying; but that’s not all. A sturdy system of thought might equip us better for integrated, creative thinking. When I understand how things connect, my own control over them can improve. For example, insight about human psychology will open up new ways to think about morality, and vice versa.

But ultimately, Kant found harmony important because it supports the construction of a coherent “worldview.” The English language gained that term through the translation of a German word, “Weltanschauung,” which Kant coined and which has been a focus of my own work. At its most basic, a harmonious worldview allows us to feel more at home in the world: We gain a sense of how it hangs together, and see it as imbued with meaning.

How we think ultimately determines how we live. If we have a stable abode of thought, we take that stability into everything we do and have some shelter from life’s storms.

Alexander T. Englert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Alexander T. Englert, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Richmond