Renewable energy is cheaper and healthier – so why isn’t it replacing fossil fuels faster?

- Written by Jay Gulledge, Visiting Professor of Practice in Global Affairs, University of Notre Dame; University of Tennessee

A technician walks through a solar farm in Goma, Congo, in 2025.AP Photo/Moses Sawasawa

A technician walks through a solar farm in Goma, Congo, in 2025.AP Photo/Moses SawasawaYou might not know it from the headlines, but there is some good news about the global fight against climate change.

A decade ago, the cheapest way to meet growing demand for electricity was to build more coal or natural gas power plants. Not anymore. Solar and wind power aren’t just better for the climate; they’re also less expensive today than fossil fuels at utility scale, and they’re less harmful to people’s health.

Yet renewable energy projects face headwinds, including in the world’s fast-growing developing countries. I study energy and climate solutions and their impact on society, and I see ways to overcome those challenges and expand renewable energy – but it will require international cooperation.

Falling clean energy prices

As their technologies have matured, solar power and wind power have become cheaper than coal and natural gas for utility-scale electricity generation in most areas, in large part because the fuel is free. The total global power generation from renewable sources saved US$467 billion in avoided fuel costs in 2024 alone.

As a result of falling prices, over 90% of all electricity-generating capacity added worldwide in 2024 came from clean energy sources, according to data from the International Renewable Energy Agency.

At the end of 2024, renewable energy accounted for 46% of global installed electric power capacity, with a record 585 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity added that year — about three times the total generating capacity in Texas.

Health benefits of leaving fossil fuels

Beyond affordability, replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy is healthier.

Burning coal, oil and natural gas releases tiny particles into the air along with toxic gases; these pollutants can make people sick. A recent study found air pollution from fossil fuels causes an estimated 5 million deaths worldwide a year, based on 2019 data.

For example, using natural gas to fuel stoves and other appliances releases benzene, a known carcinogen. The health risks of this exposure in some homes has been found to be comparable to secondhand tobacco smoke. Natural gas combustion has also been linked to childhood asthma, with an estimated 12.7% of U.S. childhood asthma cases attributable to gas stoves, according to one study.

Fossil fuels are also the leading sources of climate-warming greenhouse gases. When they’re burned to generate electricity or run factories, vehicles and appliances, they release carbon dioxide and other gases that accumulate in the atmosphere and trap heat near the Earth’s surface. That accumulation has been raising global temperatures and causing more heat stress, respiratory illnesses and the spread of disease.

Electrifying buildings, cars and appliances, and powering them with renewable energy, reduces these air pollutants while slowing climate change.

So what’s the problem?

In spite of the demonstrated economic and health benefits of transitioning to renewable energy, regulatory inertia, political gridlock and a lack of investment are holding back renewable energy deployment in much of the world.

In the United States, for example, major energy projects take an average of 4.5 years to permit, and approval of new transmission lines can take a decade or longer. A large majority of planned new power projects in the U.S. use solar power, and these delays are slowing the deployment of renewable energy.

The 2024 Energy Permitting Reform Act introduced by Sens. Joe Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, and John Barrasso, a Republican from Wyoming, to speed approvals failed to pass. Manchin called it “just another example of politics getting in the way of doing what’s best for the country.”

An even bigger challenge faces developing countries whose economies are growing fast.

These countries need to meet soaring energy demand. The International Energy Agency expects emerging economies to account for 85% of added electricity demand from 2025 through 2027. Yet renewable energy development lags in most of them. The main reason is the high price of financing renewable energy construction.

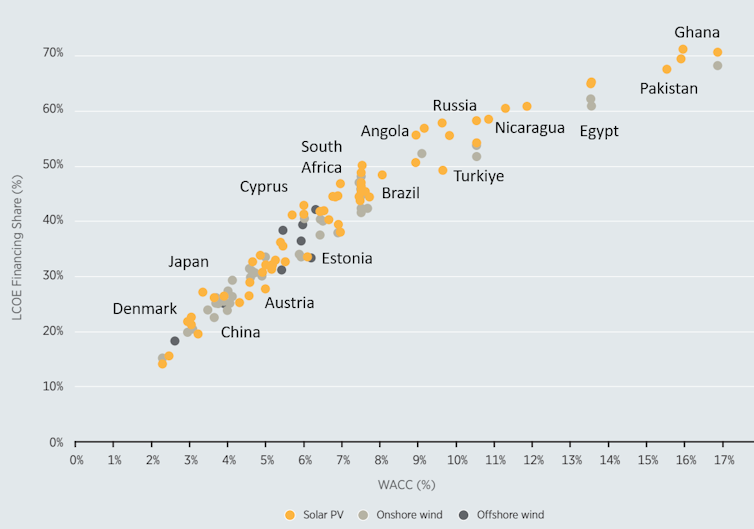

Most of the cost of a renewable energy project is incurred up front in construction. Savings occur over its lifetime because it has no fuel costs. As a result, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for those projects varies depending on the cost of financing to build them. The chart shows what happens when borrowing costs are higher in developed countries. It illustrates the share of financing in each project’s levelized cost of energy in 2024 versus the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The yellow dots are solar projects; black and gray are offshore and onshore wind.Adapted from IRENA, 2025, CC BY

Most of the cost of a renewable energy project is incurred up front in construction. Savings occur over its lifetime because it has no fuel costs. As a result, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for those projects varies depending on the cost of financing to build them. The chart shows what happens when borrowing costs are higher in developed countries. It illustrates the share of financing in each project’s levelized cost of energy in 2024 versus the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The yellow dots are solar projects; black and gray are offshore and onshore wind.Adapted from IRENA, 2025, CC BYIn many developing countries, wind and solar projects cost more to finance than coal or gas. Fossil projects have a longer history, and financial and policy mechanisms have been developed over decades to lower lender risk for those projects. These include government payment guarantees, stable fuel contracts and long-term revenue deals that help guarantee the lender will be repaid.

Both lenders and governments have less experience with renewable energy projects. As a result, these projects often come with weaker government guarantees. This raises the risk to lenders, so they charge higher interest rates, making renewable projects more expensive upfront, even if the projects have lower lifetime costs.

To lower borrowing costs, governments and international development banks can take steps to make renewable projects a safer bet for investors. For example, they can keep energy policies stable and use public funds or insurance to cover part of the lenders’ investment risk.

China produces the vast majority of solar cells sold worldwide. The Chinese government has also built renewable energy projects in many Latin America countries and other developing regions.AFP via Getty Images

China produces the vast majority of solar cells sold worldwide. The Chinese government has also built renewable energy projects in many Latin America countries and other developing regions.AFP via Getty ImagesWhen investors trust they’ll get paid, interest rates drop dramatically and renewable energy becomes the cheaper option.

Without international cooperation to lower finance costs, developing economies could miss out on the renewable-energy revolution and lock in decades of growing greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, making climate change worse.

The path ahead

To avoid the worst effects of climate change, countries have agreed to cut their greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades.

Achieving this goal won’t be easy, but it is significantly less difficult now that renewable energy is more affordable over the long run than fossil fuels.

Switching the world’s power supply to renewable energy and electrifying buildings and local transportation would cut about half of today’s greenhouse-gas emissions. The other half comes from sectors where it is harder to cut emissions — steel, cement and chemical production, aviation and shipping, and agriculture and land use. Solutions are being developed but need time to mature. Good governance, political support and accessible finance will be critical for these sectors as well.

The transition to renewable energy offers big economic and health benefits alongside lower climate risks — if countries can overcome political obstacles at home and cooperate to expand financing for developing economies.

Jay Gulledge is affiliated with PSE Healthy Energy

Authors: Jay Gulledge, Visiting Professor of Practice in Global Affairs, University of Notre Dame; University of Tennessee